A few Saturdays ago, I found myself in the unusual position of having three full hours at home alone, family temporarily scattered around Manhattan, and I took the opportunity to do something I hadn’t done in years: listen to the live Metropolitan Opera broadcast on WQXR. Turning up the volume on the stereo, I sat back to enjoy Umberto Giordano’s 1898 Fedora, which hadn’t been produced at the Met since 1996 but was recently revived at its New Year’s Eve gala.

Some things never change. Though this performance lacked the usual intermission “Opera Quiz,” there was the usual chirpy back and forth between the hosts and interviews with the lead singers during the act break. A part of this chirping was the reading of a synopsis of the opera, and as my Italian is non-existent, I closed my eyes as the opera ran and found that it took no real effort to follow the plot through the singing and the music once I had the broad outlines in mind; both singers and orchestra were lush and lovely, even though in the broad scheme of things Fedora is little more than a torrid potboiler typical of its verismo period. Its geographical range is broad too, reaching from a St. Petersburg salon in Act I through Paris in Act II to the Swiss Alps in Act III. Susan Youens’ program notes argue for a much more profound interpretation of the opera, to wit:

The Savoy region of France was a bone of contention in 1860 between Napoleon III’s France and the recent republic of Switzerland, whose peace and prosperity stood in contrast to many other countries. Russia and France had a history of fraught relations, with the War of 1812 not long past, but formed an alliance in the 1890s driven by shared fear of Germany’s growing ambitions. Poland had no independent existence from 1795 to 1918, being split between Prussia, the Habsburg Empire, and Russia, and Russia was increasingly riven by Tsarist and anti-Tsarist forces throughout the fin de siècle. Ultimately, love and laughter are put to an end at the close of Fedora by exile and repression, execution and tyranny — just as they too often have been in the real world.

To which I could only respond: “Nice try” — it was a potboiler and a pretty substandard murder mystery to boot. But it was fun.

In the first, 1956 edition of his Opera as Drama, still a noted critical work in operatic circles, Joseph Kerman called Tosca, another opera of the verismo period, a “shabby little shocker,” a characterization that still raises hackles among Puccini enthusiasts, and it’s not a far stretch to characterize Fedora with the same words. But Fedora once and Tosca now-and-forever-more held substantial attraction for opera houses, and I do wonder if had I watched Giordano’s opera at the Met (or on the screen as part of the Met’s live-in-movie-theatres simulcasts) my response may have been more sympathetic. For opera, like theatre, is a performance, an expensive, often luxurious display of not only vocal and musical but also visual splendor. (It is also, unlike a radio broadcast, expensive, and I would have needed many more free hours to get up to Lincoln Center to see it.)

But listening to an opera and watching it in live performance is a difference in kind, not in degree. A sensitive listener can picture to themselves a stage action, as well as characters, scenery, and lighting effects, as they experience the vocal and instrumental music aurally; the same holds true for the reader of a play, who puts in their mind’s eye, through imagination, the activity that it describes, and may even “hear” the words they read as if the words were spoken. (Indeed, those with the training to “read” music may also “hear” the music as they peruse the score.) The experience of an opera recording is not inferior to the experience of watching an opera performance — it is different, and it has its own virtues, virtues unique to the experience.

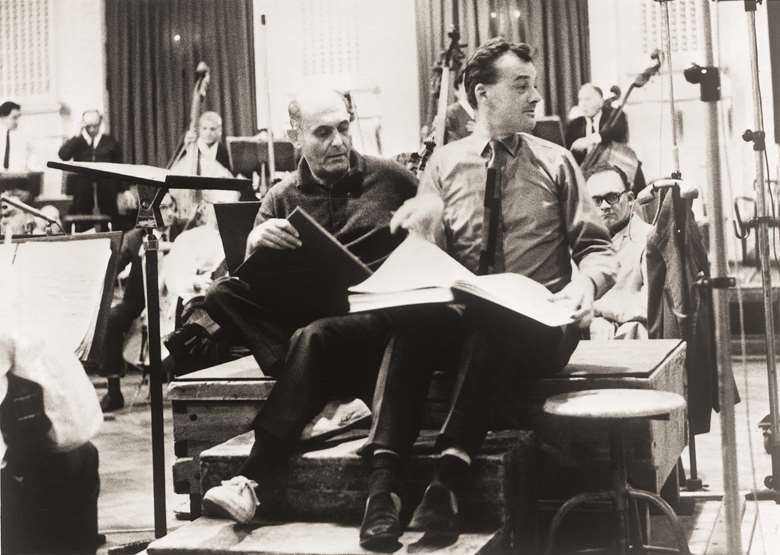

I came to Fedora after revisiting a few of Wagner’s operas in the landmark Solti recording, and I recently re-read King Lear. Though I did both in the privacy of my own home, I discovered new qualities in these works I hadn’t recognized before, perhaps as the result of my own increasing age and more mature (for want of a better word) experiences. I’m encouraged to further explorations — maybe re-explorations is also a better word — but thankful to Giordano’s shabby little shocker for this new encouragement, whether or not it gets me out of the house on a regular basis. As it happens, Kerman goes on to cite passages from two of his contemporaries, Eric Bentley and Francis Fergusson, who focused on poetic rather than operatic drama, which then sent me back to their books. So, perhaps more here, as the days go on.