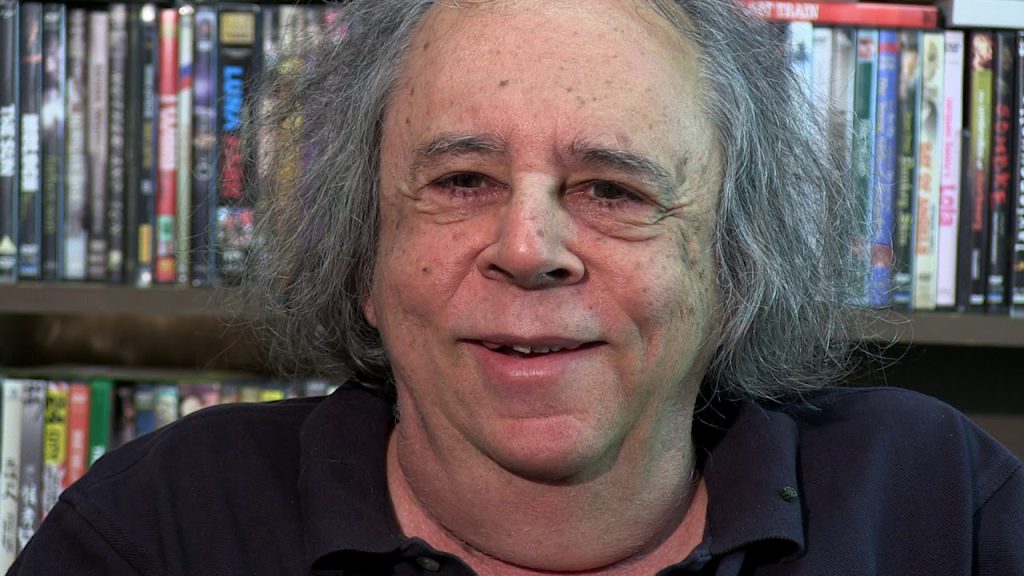

One night in 2003, I showed up at the Ontological-Hysteric Theater at St. Mark’s Church in the Bowery for Panic! (How to Be Happy!), that year’s offering from Richard Foreman. The year before I’d first visited the theater for Maria del Bosco and written — quite enthusiastically, I suppose — at my blog about my experience. But on that 2003 occasion I went to the box office to pick up my tickets; standing next to it were Foreman (instantly recognizable — rumor had it that he’d been in the running for the role of Mary Wilkes’ ex-husband, the “homunculus,” in Woody Allen’s Manhattan, a part that eventually went to Foreman’s downtown playwright colleague Wallace Shawn) and his wife, Kate Manheim. When I mentioned my name to the box office manager to retrieve my tickets, Foreman walked over to me and said, “I’ve been waiting for you! I’m Richard Foreman. I really appreciate what you’ve been writing about my work.”

To say I was flabbergasted at this would be to understate my reaction, but as I came to know Richard over the following years, I came to realize that I was no exception. I mean, why should he care what I wrote? I was no academic, nor was I a member of the professional critical class — I maintained a modest little blog, for crying out loud. But among his most memorable qualities — he shuffled off this mortal coil just this past Saturday, January 4 — was a generosity, kindness, and acceptance of the human condition that affected all those who knew him.

Over the years that followed, I wrote more about Richard’s work, following up on my early enthusiasm for his production of The Threepenny Opera at Lincoln Center in 1976. (That same day, in the afternoon, I saw Gielgud and Richardson in the New York premiere of Harold Pinter’s No Man’s Land. That was quite a Saturday.) A trip to the Drama Book Shop then rewarded me with his first collection, Richard Foreman: Plays and Manifestos (New York University Press), which had just been published and a copy of which is at my side as I write this.

I saw most of Richard’s work that followed Maria del Bosco; we met infrequently but always pleasantly for coffee and conversation after that; he was kind enough to attend the premiere of one of my own plays a few years later, followed by his enthusiastic approval; we casually discussed the possibility of my writing some kind of biography of him — a project that, thankfully for both of us, never panned out; and even today the home page for his Ontological-Hysteric Theater memorializes a 2015 celebration of his work that I moderated with Richard and his long-time friend, filmmaker Ken Jordan. I never really recovered from that initial excitement of our first meeting, and I recall the near impossibility of “moderating” such an entertaining, self-effacing raconteur.

(I also remember talking to Richard about my attending one of his productions; I told him I’d try to do so on the date he suggested, but it all depended on whether I could get a babysitter for my two young children. “Bring the kids!” Richard said. “Children love my plays!”)

My writing about Richard’s work was an attempt to come to terms with his extraordinary sense of the possibilities of theater for the individual consciousness. As a writer — as any writer, I suppose — I felt the need to articulate just what it was in my experience of the world that led me to my own reaction, and this included my experience of Foreman’s constructed theatrical world.

What made his theater so special and revolutionary was his attempt to undermine every single moment of a traditional theatrical experience, from character and plot to light and sound, to radically disorient the spectator, throwing that spectator back on his or her own emotional, intellectual, and spiritual resources. What a character said violently contradicted what a character did; stasis would be interrupted by physical, visual, and aural dance and chaos; and all of this was centered in the experience of the live human body, speaking, singing, dancing, and talking. As Foreman sat, Godlike, on a throne held together by duct tape during the performance, cuing light and sound himself across a phantasmagoric, P.T. Barnum-style spectacle of wavering perspective, he was never really in control, just as we’re never fully in control of the world as it presents itself to us.

All of this was in the service of sensual liberation: to perceive the world anew, and to realize that the world was what we made of it as individuals. Throwing off the shibboleths and cliches of a constructed world made for us by religion or politics or corporations or tradition, we were encouraged to make a world for ourselves. Needless to say, for Richard, this had — or, at least, could have — profound political, social, cultural, and sensual consequences for every single spectator. If 100 people sat in his theater watching Maria del Bosco, they saw 100 different plays; the same could be said for any play, I suppose, but that truth was never at the center of the deliberate aesthetic program as it was for Richard.

This was a profound challenge not only to the theatergoer, but the critic too, and everybody else. Our success or failure at meeting this challenge was entirely up to us. Of course, Richard himself put it best, in his Unbalancing Acts: Foundations for a Theater:

But I want a theater that frustrates our habitual way of seeing, and by so doing, frees the impulse from the objects in our culture to which it is invariably linked. I want to demagnetize impulse from the objects it becomes attached to. We rarely allow ourselves the psychic detachment from habit that would allow us to perceive the impulse as it rises inside us, unconnected to the objects we desire. But it’s impulse that’s primary, not the object we’ve been trained to fix it upon. It is the impulse that is your deep truth, not the object that seems to call it forth. The impulse is the vibrating, lively thing that you really are. And that is what I want to return to: the very thing you really are.

I have only to add that Richard changed my life — as he changed the lives of so many others — and that I’ve looked at the world differently since being exposed to his plays and his person. A glass raised, then, to his memory.

Below is a collection of my writings about Richard and his work that I put together not long ago.

I stopped writing about theatre a decade ago, around the same time that Richard Foreman retired from the stage. I’ve been back to the theatre a few times since then, but I haven’t yet come across theatrical experiences quite as liberating as Foreman’s plays. His work was something of an acquired taste, perhaps, but I had no problem acquiring it. I can’t remember walking out of one of Foreman’s Ontological-Hysteric productions at St. Mark’s Church without having a newfound awareness of the world and my place in it.

So the below is something of a souvenir of my theatre criticism days, a collection of my notes, reviews, and short essays about the work of Richard Foreman. These were written over a period of many years, and I’ve made no attempt to organize or polish them. (A somewhat more organized presentation of the same ideas constitutes my introduction to Plays with Films, a 2013 collection of his late-period plays from Contra Mundum Press.) I am cheered to remember that Foreman himself found them thoughtful. You can find his more recent video and film work here.

One of the revolutions theorized in a new Theatre of Revolt must be a revolution not only in society or politics, but also in the realm of consciousness: in the perspective from which one sees the world and approaches the material from which one constructs it. Richard Foreman (b. 1937), in this sense, must be among most radical of the dramatists of such a theatre. Since 1968 and the foundation of his Ontological-Hysteric Theater (which closed its doors a few years ago), Foreman’s project has been to take Brecht’s efforts to contemplate and reconsider conventional perceptions of reality and, utilizing may of the same estranging techniques, transform them into metaphysical speculations about how to interpret and engage with the world. If Brecht hoped to undermine capitalism and fascism, Foreman undermines the given structure of the world itself in a liberating project to see it and human possibility anew.

Foreman turns epistemology into slapstick comedy: the objective world is the banana peel on which the individual subject is constantly slipping, with ensuing perceptual pratfalls. Foreman’s landscapes, then, have over the years become more and more littered with barriers and perverse intrusions of the natural world. The urge of the human being to dominate his environment turns the Foreman character into a miles gloriosus, striding across the stage with firm confidence and conviction, only to be tripped up by the untied shoelaces of his own imperfections. The strong erotic element of Foreman’s plays reveals the feminine as the possessor of an uncertainty that nonetheless provides metaphysical truth and the ability to forego domination: instead, she remains open to new experience, even as that experience may be denied by an oppressive masculinity.

But does this experience necessarily come at a price? If so, it is a low one: it is only the confidence that one is always right that must be repudiated. The desiring will operating through the body guarantees that stasis is not possible: frenetic activity on Foreman’s stage is not always chaos, but sometimes a canvas from which the subject can pick and choose significances and meanings. Even so, anxiety cripples many Foreman characters, at least early in the plays, but more often than not one or more characters sees a light at the final curtain: not certainty, perhaps, but a new perspective that allows reinterpretation and liberation: the self, even if it constantly changes, is at least finally whole. This is a form of reconciliation with the world that permits creativity for new selves and new worlds.

Because his interest is in the individual subject, Foreman has always been an internationalist; his plays have sometimes found more success in Europe, especially Austria and France, than in the U.S. The final three plays at his Ontological-Hysteric Theatre acknowledged not only the shrinking world (in which space itself, one of the Kantian a priori categories of experience, is foreshortened and disguised) but also its mediation through digital technology. As human perception stretches across the oceans in this artificial manner, he suggests that the spread of the subjective imagination may be accompanied by a consequent loss of depth in the human character, as the subject engages more and more in two-dimensional representational simulacra of the Other. We face not other individuals, but screens, mistaking the binary digits of the aptly-named digital world for depth. The content of these surfaces consists of both less than the individual and more than the image: another mechanical banana peel which threatens the equilibrium of the subject. Globalization has had both laudatory and destructive effects on economies, cultures and nations Foreman suggests it’s had both of those effects on the individual subject as well. His exploration of these effects contributes to a world theatre in which traditional forms of drama seem pathetically inadequate and places Foreman among those dramatists who work to determine a form of revolutionary theatre that suits the new century.

Angelface (1968)

Presented by the Ontological-Hysteric Theater at the Cinematheque (80 Wooster Street), New York City, April 1968. In Richard Foreman: Plays and Manifestos, edited and with an introduction by Kate Davy. New York: New York University Press, 1976, pp. 1-31.

The ostensible event at the center of Foreman’s first play for his Ontological-Hysteric Theater is a wedding, that most domestic and intimate ceremony, but the ceremony itself is not explicitly presented. Instead, it gives rise to an anxiety that circulates among all the characters, but most especially Max, who exists in a state of spiritual paralysis that grows only more acute as the play progresses through its five scenes. While no relationship or identity in the play is certain, Max may be Rhoda’s brother — and may also be Rhoda’s guardian angel (13).

What may be most fearful about Max is his imagination. At the end of the first scene, Max’s imagination is inflamed (and enflamed) by Walter’s suggestion “I think of [these walls] on fire,” turning it into disaster. “Set this room on fire, what happens?” Max responds. “I’m on fire, Rhoda’s on fire — ” (7) And, at the end of the first scene, this imagination becomes apocalyptic; Max imagines “tongues of flames,” and Walter tells himself, “I’m gonna keep Max under observation.” (8) Max stays under observation — even self-observation — through the rest of Angelface.

The leap between an original moment of that perception and what the human mind, the imagination, can do with that moment is suggested in the first scene of the play: Can the imagination open a closed door, or even re-open an open door a second, third, fourth time? How this imagination affects our movements in the world through those mind-mechanics is a question that hovers all of Foreman’s plays; and there is a reaching, a desire, for the mystical state even here. By the end of the play, Max’s body is even more paralyzed than at the beginning — scene one opens with Max’s voluntary stillness, the end of scene five finds him “now tied up, a rope around his shoulders lifting him toward the ceiling, until only his extended toes manage to touch the carpet” — but he laughs nonetheless; when Walter notes that “You look happy,” Max responds, “Yes.” (30)

The event of a wedding lends these seemingly abstract conceptions a very real, even erotic quality. Walter becomes divided in the play between Walter I and Walter II, the first a cheap, vaudeville guardian angel with “gigantic wooden wings, strapped onto his back, angel fashion” (19), the source of much of the play’s slapstick qualities (and the play is rife with physical comedy), the second weighted down to the floor. But this all happens, it seems, as the result of Max’s mental mechinations, or at least he thinks it does (“Everybody happy about what I just did, huh?” he says at the conclusion of the slapstick scene three). The division between what is possible on the stage in this stripped-down conception of drama and theatre, eschewing plot for a moment-by-moment examination of what comprises temporality itself, and what is possible in the world itself is mirrored in the relation between the mind and the body, if each body’s movement through space, real and imaginary, was similarly subjected to that atomic observation.

There are other aspects of the play which point the way forward to Foreman’s future investigations, here seen in embryo. The sisters Agatha and Rhoda are far more imaginatively free than the male characters of the play, and Rhoda especially is introduced here as Foreman’s most energetic adventurer through his world. At the end of scene four, she participates in the trust-fall familiar to all first-year acting students, letting herself fall backwards out the window and into the arms, perhaps, of a waiting guardian angel (“I’m floating,” she says with a laugh as she’s suspended outside of the window [28]). The power of language, even a name, to transform a situation into something its opposite, is noted by Max in scene two:

Rhoda is participating right this minute. I NAME Rhoda — it makes the chairs and tables start shaking. “Rhoda.” A word acts like a knife, huh? Look at the woodwork. (12)

And even the perspectivity provided by Foreman’s later use of dotted string is introduced — “Rays of light … dotted lines between the three of us,” Walter I suggests (23) — through it would of course become much more literal later on.

First produced at Jonas Mekas’s Cinematheque in 1968, Angelface reveals the aesthetics of the structural films of Michael Snow and others, but written and staged for theatrical performance. As in Snow’s Wavelength, first shown in 1967, a year before Angelface, there’s a dynamic between the individual cellular nature of time (each second divided into 24 separate photographs in the case of film) and the seeming eternal longevity of time itself, also revealed as the perceiver, over that time, traverses a space (a loft, in the case of Wavelength) or an event (a wedding, in the case of Angelface). This same examination of time and mortality, and what the imagination can do to it as well as the objects and persons shaped by time, requires a new approach to theatre. Angelface may be a first step on that path, but it’s a confident and promising step; and Foreman’s later work would reveal a myriad of possibilities for its presentation.

Total Recall (1970)

Subtitled Sophia=(Wisdom): Part 2. Presented by the Ontological-Hysteric Theater at the Cinematheque (80 Wooster Street), New York City, December 1970–January 1971. In Richard Foreman: Plays and Manifestos, edited and with an introduction by Kate Davy. New York: New York University Press, 1976, pp. 33-66.

Neither the light-bringing goddess Sophia nor his wife Hannah seems to be particularly well-disposed to Ben at the beginning of Total Recall, Foreman’s third Ontological-Hysteric play. Ben himself is experiencing something of a phenomenological crisis: “Nothing seems different this morning. I sit down to breakfast. I have coffee and rolls. Then I put on my coat and go out into the street. Nothing seems different,” he says (34). But oh, it is, and even he knows it. He has some kind of revelation, and the rest of the play is an exploration of just what may have been revealed. He hopes to find it in a kind of “total recall,” a memory of what happened, but it eludes his grasp; instead, his vision doubles, redoubles, then returns to “normal” again.

This is Foreman’s first explicit experimentation with the frame as a device for perception and directing attention; apart from the proscenium opening, the frames are multiple. There is not only a window frame (through which characters fall, both into and out of the room, through the play), but also a “landscape box” and two “puppet theatres,” as well as a box which displays the goddess and her lamp, that the characters contemplate from time to time; even the perspectives within these smaller frames change. Sometimes the perspective is a landscape; at other times, Ben thrusts his hands through the curtains of the puppet theatres, hands gargantuan compared to the landscapes and whatever puppets may theoretically appear inside.

But more to the point, the body and the mind are themselves frames, and their experience is asychronous: what Ben’s body feels and what his mind perceives or thinks seem detached from each other. Wisdom inheres in being able to think with the body and feel with the mind, a wisdom that comes to Ben late in the play and even provides a means for him to erotically communicate with his rather wiser wife Hannah. The mind and the body provide frames for experience — perspectives — as well, sometimes one upon the other, and as Ben negotiates these perspectives he begins to find a new sensual life. At best, the body can emanate the same light, the same wisdom, as Sophia’s lamp. It’s maintaining that light, that wisdom, that’s the hard part.

The explicit use of landscapes in the puppet theatres is an explicit reference to Stein, but I detect a Chekhovian note here, too: an emphasis on the quotidian, as Ben describes in his opening monologue. We may as well be in a Chekhov play: it’s a family scene, with husband Ben, wife Hannah, uncle Leo, and even a little girl and a dog wandering around with seeming aimlessness. It’s an aimlessness that, in the 1970 production, transpired over three hours. As Arthur Sainer wrote in his review of the play for the Village Voice, “Foreman’s focus is on what begins as the commonplace. A plain kitchen table, a couple of plain wooden chairs, a plain bed, a plain tree, a plain husband.” Sainer also quotes Foreman’s own comment on the play: “If every moment can be clear and only itself, the stasis becomes a tremendous release from fantasy and storytelling. And delight is in everybody’s head instead of in objects and various postulated adventures.” (“Arthur Sainer on Total Recall,” in Richard Foreman, edited by Gerald Rabkin. Baltimore and London: A PAJ Book from the Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999, pp. 67-68.) The loud noise that punctuates the play, described as “the workings of an electric saw brought up to the highest decibel,” serve to shatter any sense of adventure or narrative and return the attention to the precise moment under consideration on the stage, encouraging a clear and “only itself” perspective.

The third production of the Ontological-Hysteric Theater (the text for the second, 1969’s Ida-Eyed, is not in print), Total Recall may also have been the last were it not for that Arthur Sainer review. In a 1990 interview with Ken Jordan, Foreman remembers the effect the review had on his effort:

I will be eternally grateful because for Total Recall he wrote a long review saying: Well, this is pretty hard to take, and I am against most critics who give consumer guides, and though I usually don’t do this I’ve got to say you must go see this play because it’s like nothing I’ve ever seen, and it’s terribly important. People still kept walking out, of course. But he reviewed my plays for the next couple years, and was very favorably inclined. If he hadn’t done that, I often wonder if I would have had the courage or the determination to continue, because I was a very sensitive young thing and, really, everybody walked out. Including … I had a few friends like Annette Michaelson who would direct artists to see my plays, and I remember the nights that Richard Serra and Robert Morris walked out. And that crushed me. Later, when I got to be friendly with them, they told me, “Oh, well, yeah, in those days your work was so abstract, and I’m not really interested in abstract art!” [Laughs] But at the same time, though, we thought that we had the word, and obviously these … of course these people couldn’t appreciate it, just like they couldn’t appreciate Van Gogh, or whoever you want to name. So we felt quite heroic. And fortunately there were a few people who I really believed in who thought the work was magnificent. That was enough for me.

“Ontological-Hysteric Manifesto I” (April 1972)

In Richard Foreman, The Manifestos and Essays. New York: Theatre Communications Group, 2013. Pp. 3-16.

1971–Lenox, summer. I sit, at sunrise, and stare out into the trees, listening to the birds– i.e. 100 invisible birds in counterpoint. My head, savoring that interweaving of themes, performs in a good way–performs in the way that heretofore I have felt art should make it perform. But suddenly (drama!) that often-before entertained notion crystallizes in my head in such a way that a chapter ends, the book closes, and I have no more interest (no more risk, no more “unknown”) in such an art based on counter-point & relationship. What can replace it? Don’t know…. The painters have discovered “shape.” What can the theater discover?

When Foreman’s quasi-epiphany took place at the Lenox Arts Center in Lenox, MA, where he was directing Dream Tantras for Western Massachusetts, he had already presented Angelface, Total Recall, and several other plays through his Ontological-Hysteric Theater in New York; his ideas now solidified enough to result in the first “Ontological-Hysteric Manifesto,” which Foreman completed in April 1972. Like the manifestos of the Fluxus movement, Foreman’s polemic was itself both theory and practice — a deliberately hand-made 13-page call for meditation and a kind of revolution, littered with doodles and shapes that both illustrated and played against the typewritten text. It both looked back to his past work and forward to the rest of his career, several of its ideas continuing to inform his practice.

It is not surprising either that, like other manifestos, it takes a strong stand regarding the kinds of theatre and art he was rebelling against, in both traditional and avant-garde forms. He simultaneously rejected the aleatoric practices of John Cage and others — “chance & accident & the arbitrary — which we reject because within too short a time such choice so determined becomes equally predictable as ‘item produced by chance, accident, etc.'” — as well as the work of Peter Brook and Jerzy Grotowski, which had visited American shores by the time he wrote the manifesto:

1967– Suddenly the theater seems ridiculous in all its manifestations and continues to do so in 1971. I.e., Peter Brook staged Midsummer Night’s Dream. The actors enter onstage and immediately, the absurdity– as Stella, Judd, et al. realized several ears ago…one must reject composition in favor of shape (or something else)… Why? Because the resonance must be between the head and the object. The resonance between the elements of the object is now a DEAD THING.

Referencing Minimalist painters Frank Stella and Donald Judd, Foreman’s attempt to strip theatre of its traditional forms of composition in favor of reinvigorating “resonance between the elements of the object” reflected the stasis of many of Foreman’s stage presentations; whatever happened in the theatre happened in the eye of the spectator rather than the traditional structures of stage action and practice. “The work of art as a contest between object (or process) and viewer,” Foreman wrote. “Old notions of drama (up thru Grotowski-Brook-Chaikin= the danger of circumstance turning in such a way that we are ‘trapped’ in an emotional commitment of one sort or another.” It was not that Foreman dismissed emotion entirely, only the trap of commitment that traditional theatre practice represented for him.

Foreman’s response in this first manifesto of three was to posit an art that serves two “essential, related functions”: that of evidence (the work of art serving as an example to others, “to give courage to ourself and others to be alive from moment to moment”) and of an ordeal to reach a certain kind of clarity of perception:

But CLARITY is so difficult in the smallest steps from one moment to the next, because on the miniscule level, clarity is muddled either by the “logic” of progression (which is really a form of sleepwalking) or by the predictability of the opposite choice– the surreal-absurdist choice of the arbitrary & accidental & haphazard step. Of course ORDEAL is the only experience that remains. And clarity is the mode in which the ordeal becomes ecstatic.

The Ontological-Hysteric project then became a metaphysical process as well: to reclaim the validity of the subject as the maker of meaning, rather than the object imposing its presumed and illusory meaning and structure on the subject. Foreman’s plays were examples of the individual subject at work and play in the field of experience. It wasn’t that Foreman offered a “third way” between the traditional and avant-garde theatre of the time, but that he offered a multiplicity of ways — an individual way of perceiving and meaning-making for each individual spectator. The first manifesto closed with a challenge in the form of a dramatic moment:

BEN: Oh well. (Pause.) Make something.

ALL: Can you describe it, Ben?

The challenge, of course, was one that Foreman imposed upon itself, in both his theory and practice, but the challenge extended to the spectator as well — as both example and ordeal.

Pain(t) (1974)

Presented at 141 Wooster Street, New York City, April-May 1974. In Richard Foreman: Plays and Manifestos, edited and with an introduction by Kate Davy. New York: New York University Press, 1976, pp. 195-206.

This play concerns itself with a certain kind of energy that is the energy that most people use most of the time. (I.E. the wrong energy).

“Once upon a time a young woman from the Provinces came to the city to try and gain fame as a great artist. Upon meeting the leading paintress of her day, she realized that to replace that talented lady in the public’s eye would be difficult indeed. In the meantime, a man of culture and breeding suggested she fill the time between dream and achievement by helping to give physical form to certain fantasies which in that gentleman’s mind sometimes related to art and sometimes didn’t. She agreed, rationalizing to herself ‘Oh well, it’s all in the mind, isn’t it…?'”

Program note for Pain(t)

–Ancient French fable

Kate Manheim joined the Ontological-Hysteric Theater in December 1971 as an angel in HcOhTiEnLa (or) Hotel China, but with the next production, 1972’s Sophia=(Wisdom) Part 3: The Cliffs, she made her debut as Rhoda, a recurring character who came to serve as an on-stage surrogate for Foreman himself (at least, certain parts of him). Perhaps the most important quality that she brought to Foreman’s work was an intense female erotic energy, an energy that profoundly informed the 1974 play Pain(t), one of Foreman’s first works to foreground artistic creation and the artist-performer-spectator dynamic.

One of the central themes of the play, the tension of distance and intimacy in sexual and aesthetic relationships, emerges early on. Eleanor visits Rhoda in Rhoda’s studio, where she almost instantly gauges the intensity of artistic experience as both creator and spectator:

ELEANOR (Pause. Shows her arm.) Look. I got some paint on my arm.

RHODA (Shows elbows.) Wash your elbows.

ELEANOR No, I got it on the inside of my arm. (Turns her arm.)

RHODA How come.

ELEANOR That’s where the blood is.

As the play develops, Rhoda is more and more challenged by the effort of approaching her art and Eleanor as a potential lover, frustrated ever more by the impossibility of bridging the distance between intention and creation, telling Ida, “I can match each part of my body to a part of your body … It’s like looking into a mirror”; it’s also paralleled by sexual frustration, a frustration that doesn’t seem to affect Eleanor in the slightest as she takes Max for a lover. Rhoda is jealous, perhaps that she can’t replicate this erotic intensity in her art:

ELEANOR Oh Rhoda, if you came closer.

RHODA If I came closer I’d want to hurt you.

ELEANOR I’d want to hurt you too.

RHODA How come. (Pause.) Correction, we made a mistake including distance in it.

Pain(t), as it transpires, subjects the theatrical experience to the same anxieties as the sexual experience; experience and memory, for both Rhoda and the audience for Pain(t), become unreliable, and the ecstasy of a moment can disappear in the next moment, unrecoverable. The artist experiences a frustrating distance from her work (“There doesn’t seem any longer to be a relation between my paintbrush and the picture that comes out of it,” Rhoda says late in the play), and the audience is also forced away from the characters. In scene five, a “Voice” makes this explicit, noting, “Oh spectator, your relation is different to the body that is amongst you” as “beams extend Ida’s arms into the seating section where spectators are.” Extant photos of the production by Kate Davy and Babette Mangolte depict the extraordinarily sensual and erotic character of the production (a few of Mangolte’s can be found here), several of the female characters naked and wearing high heels, but the final moment of the production is a statement from Voice that pushes the audience even farther at arm’s (or beam’s) length, frustrating erotic longing and desire as well as aesthetic interpretation: “The play’s over. You’re left with your own thoughts. Can you really get interested in them or are they just occurring.”

A profoundly erotic and philosophical work, Pain(t) outlines the possibility (or threat?) of sexual and spiritual imagination to merge body and personality among lovers and between the subject and object of aesthetic experience; it may also have been the last of the plays of Foreman’s early minimalist period, before he explored more baroque staging techniques that would serve to emphasize his work’s essential sensuality. In Pain(t), lovers and artists and models alternately caress each other and violently fight with each other, and there is a melancholy resignation that the physical world as it is can’t permit the ecstatic possibilities of that sexual and spiritual imagination; those ecstasies occur on another, perhaps a higher, plane. Pain(t) may be the masterpiece of Foreman’s early career.

The Gods Are Pounding My Head! (aka Lumberjack Messiah) (2005)

Let us now consider Pity, asking ourselves what things excite pity, and for what persons, and in what states of our mind pity is felt. Pity may be defined as a feeling of pain caused by the sight of some evil, destructive or painful, which befalls one who does not deserve it, and which we might expect to befall ourselves or some friend of ours, and moreover to befall us soon. And, generally, we feel pity whenever we are in the condition of remembering that similar misfortunes have happened to us or ours, or expecting them to happen in the future.

Aristotle (tr. Roberts), Rhetoric 1386a-b

Compared to his plays of the last few years, Richard Foreman’s latest, The Gods Are Pounding My Head! (aka Lumberjack Messiah), is spare and more textually written than usual. The stage design is pared down: still an object-filled consciousness, but not as crowded as, say, the design for Panic! or King Cowboy Rufus Rules the Universe. The text is still gnomic, but richly textured, with extended reference to the great 19th century poet of the Middle Industrial Age Alfred Lord Tennyson and imagery of the heart, nature and stars that reaches back to the German Romantics. More, it marks the end of a cycle of production of at-arm’s-length chamber dramas that started with Bad Boy Nietzsche (2000).

In the development of Foreman’s body of work, this cycle marks a growing consciousness of the tragic relations between subject and object, relations which seem more and more phenomenological than ontological. Foreman’s early plays, from the 1968 Angelface to the 1975 Rhoda in Potatoland, examined the quality and quantity of perception: for character Rhoda to perceive a character Sophia in the middle of her room was not ontologically different from Rhoda perceiving a large potato; what’s more, Rhoda could project her subjective obsessions (including her Jungian animus) onto the potato as well as she could on Sophia without changing the essential potato-ness of the spuddy object.

This tips our sympathy as audience towards a recognition of the soul (if such a word is appropriate) of the organic world outside of us. We can only know a potato if we can recognize an essential element of its a priori being. In Schopenhauerian terms, this is the will, the unconscious essence of all noumenal existence that expresses itself through the phenomenal object. Foreman’s great achievement in this latest cycle of plays is to find theatrical expression for this sympathy of object for object through a recognition of this inner will. As perceiving subjects who know the expression of this will most intimately through the unique objects of our own physical bodies, we can do one of two things: we can recognize this same striving, insatiable will to satiation and destruction in other objects, and we can urge its (and our own) renunciation in the service of compassion for the world; or we can, like the lumberjacks we all are, cut a swathe through experience with our phenomenal axes, levelling the constructs of the phenomenal past in an effort to allow this striving, insatiable will to fulfill its tendency to destroy.

Sometimes It Works

I come from a tradition of Western culture in which the ideal (my ideal) was the complex, dense and cathedral-like structure of the highly educated and articulate personality a man or woman who carried inside themselves a personally constructed and unique version of the entire heritage of the West.

But today, I see within us all (myself included) the replacement of complex inner density with a new kind of self evolving under the pressure of information overload and the technology of the instantly available. A new self that needs to contain less and less of an inner repertory of dense cultural inheritance as we all become pancake people spread wide and thin as we connect with that vast network of information accessed by the mere touch of a button.

Will this produce a new kind of enlightenment or super-consciousness? Sometimes I am seduced by those proclaiming so and sometimes I shrink back in horror at a world that seems to have lost the thick and multi-textured density of deeply evolved personality.

This play speaks to that anguish.

Richard Foreman, Program Note, The Gods Are Pounding My Head!

Poor Dutch, the angsting lumberjack of Foreman’s play. As performed by Jay Smith, all movement and statement is tentative and ambivalent when you’ve lost faith in the validity of the world and your own identity. It’s not a good place for a lumberjack to be, especially when you’re urged on to a reconciliation with the world by your skeptical sidekick Frenchie and the alluring siren of desire Maude, who want nothing more than to drag you back, via insult and love potion, to this phenomenal sphere.

My own mind constructs narrative as I search for meaning: stuck in the phenomenal world described by Kant and by Schopenhauer in Fourfold Root, I by my nature expect to find significance in time, space and causality. Narrative makes meaning; one thing happens because another has happened before it; succession in time and space is a form of explanation. Characters like Frenchie and Rhoda in Richard Foreman’s plays have lost their mooring in that phenomenal world, having for some reason been vouchsafed an indication of the will, of the thing-in-itself, and their own capacity for destruction and suffering.

As an avant-garde artist Foreman is unusually cognizant of Western Civ. I was surprised to see, in King Cowboy Rufus, just how indebted his work was to Racine and the Restoration dramatists. In Gods, he makes some of his most explicit references to the Judeo-Christian religious tradition, especially to sin, temptation and suffering; the stone tablets of the Old Testament commandments and the crucifixion of the New Testament’s resurrection narrative are central to Foreman’s vision in this play. Foreman, however, takes these talismans of Western Christianity seriously. They tell a truth about the use of moral and ethical force and the inevitability of suffering; they are fables about the destructive will operating through human history. In this deeply ironic vision, though, the joke is that God (and the gods of the title of the play) is unknown and unknowable. We construct meanings and narratives around a suffering which may have no meaning.

The avant-garde artist and his or her audience generally dismisses Christianity as a book which bores us and instead turn to popular culture to grant our lives narratives; in these narratives, in which transformation and transfiguration are generally dismissed as impossibilities, distraction and titillation and noise generally flatten experience and ourselves to the depth of a pancake. They are magic potions (love potions and otherwise), and at the end of The Gods Are Pounding My Head, each of the characters having been vouchsafed a glimpse of the thing-in-itself, they turn deliberately to that pancake world in an effort to re-enter the safer, more comforting milieu of the phenomenon, God bless it. They down chalice after chalice of the potion (whether it’s a love potion, Christ’s blood or a pint of Brooklyn Lager is insignificant). They either have returned to the midst of shallow illusion and wish to remain in that state, or they recognize the comfort of the shallow phenomenal world and wish to regain that state again. And sometimes, as all three characters admit at the end, that escape to shallowness works; it gives us unwarranted hope and comfort; it gives us significance.

I am a little hindered by the lack of a text of the play, but in paging through a few of Foreman’s earlier writings I find that the thoughts of the program note are echoed even in his earliest work (Foreman has remained consistent in his worldview if not in his practice). This is from the conclusion of July 1974’s Ontological-Hysteric Manifesto II:

style works on the level of the pre-conscious, where most men prefer to say oh, nobody goes THERE any more as if it were an ancient vacation place that has long since lost its clientele.

And so style attacks, with truth, where man most deeply is but where he has the least developed navigational techniques. So truth storms as style in the pre-conscious And man IS shipwrecked, unable to navigate in that storm

So he says NO! To the offending work of art.

And in saying no he says no to what he is and prefers to remain animal-man. At home in the world. Asleep in his mother’s arms. Balanced (seemingly). Whole (seemingly). Happy (seemingly).

A Dumb Joke

In one scene of The Gods Are Pounding My Head!, lumberjack Dutch compares his eyes to a pair of fried eggs (again, I’m a little confounded by the lack of a script at my side, so I can’t tell you exactly how or when this occurs); following this, the stage crew enters, each carrying a a prop frying pan on the bottom of which are pasted prop eggs, sunny side up: so much for reading things literally. While eggs can mean a lot of things (in addition to simply being eggs, not eyes), I am given momentary pause by the thought that eggs, at moments, are signs of fecundity. But then it just becomes a dumb but funny joke about literalism again.

Theater Practice Makes Perfect

Photographs of Richard Foreman’s shows, as those plays have developed over the last 37 years, indicate that whatever else has changed about them Foreman’s approach to objects (what us theater types call props or properties, words which in Foreman’s scenography have evocative definitions) has remained unique. This is also a term that gathers in the human bodies who populate these plays. His trademark dotted strings, sometimes strung from object to object, at other times just strung from floor-to-flies or wing-to-wing, play with the classical perspective of the proscenium theater and emphasize, more than any other construct, the widely differing perspectives of each individual audience member. A downstage string six feet off the ground and stretched wing-to-wing will visually connect two objects upstage from it, if you’re looking at it from one part of the audience; from another, that same string will connect two entirely different objects.

While Foreman’s plays have sometimes been described as intellectual or user-unfriendly, this technique demonstrates just how much faith Foreman has in the validity of each audience member’s approach to the aesthetic object in front of them. During performances, Foreman usually situates himself, with his sound board (a patchwork quilt of electrical tape and wires) somewhere just off-center in the audience, controlling the pace and presentation of the production, but what he sees and manipulates is a different show, phenomenologically speaking, than say an audience member on the other side of the seating area, who is connecting different objects than Foreman (or anyone else in the audience) and, much to Foreman’s chagrin (one suspects), is thereby creating a different aesthetic object in toto.

Still, one is in a theater, undergoing a theatrical experience in a world rich with objects each of which has a different and changing significance, validated merely by existing in this theatrical world. Brecht (along with Gertrude Stein a central influence on Foreman’s early work) wanted to demystify the theatrical experience, to remind audiences always that they were in a theater; the audience’s absorption in narrative and illusion, he believed, was indefensible; in no way would problems presented in a play be considered soluble so long as they remained problems of the well-defined and well-performed character. What Brecht missed in this remarkable show of bad faith was that audiences always know that they’re in a theater, no more so than in modern times, when electronic media and film have largely displaced theater from its place on the cultural map. The mere social and cultural barriers that theater places on the potential theatergoer, from high ticket prices to the hassle of making reservations to the need, in most cases, for silence, remind the theatergoer that this is an odd thing to be doing, this sitting and watching a play. The theatergoer is always aware that one is a member of this temporary community called the audience, and he or she notices that this community is dense and packed when a show is popular and rather sparse and somewhat depressing when it isn’t.

Foreman’s theater foregrounds not only this element of the theatrical experience but also the perspective of each individual theatergoer as a special subject/object, with a unique way of perceiving emotion, passion and knowledge even when presented by such a control freak as Foreman. Intellectual? User-unfriendly? One begs to differ. In fact, I’m guessing that Foreman, while celebrating the individual perspective on experience, can hardly bear to release such personal perspectives to audiences not himself.

Beginning Again and Again

One night at a performance of Panic!, I think it was, the show started only to be interrupted by Foreman himself about a minute into the performance. One of the sound cues isn’t coming in right, he announced to the audience from his perch behind the soundboard. We’re going to have to start again, from the top. Behind him, in the open light booth, the board operator turned to the audience and said in a stage whisper, He does this all the time.

Notes on Zomboid! [2006]

Mr. Foreman’s essay provides a wealth of fascinating ideas with which a neophyte like myself can fill blog entries. Here’s the first:

Again and again these days I see films and plays being promoted to audiences on the basis of the many interesting real-life subjects presented in those works.

It seems we live in a world where everyone is interested above all else in interesting subjects. But shockingly I maintain, that the desire for subjects of interesting subject matter is, in fact, an avoidance of the REAL subject of real art, which is What?

The real subject is presence itself, the scintillating presence, of any and all selected items but presented in such a way that one’s primary experience (the aesthetic experience) is to realize that the SUBJECT ITSELF doesn’t matter but is always in fact the TRIVIAL aspect of the art event.

That trivial aspect (the subject) is what we focus on when we chose NOT to be deeply engaged with what art is deeply about the full, multi-dimensional presence of whatever subject is being obliterated by the power of present-ness. However, by the usual gluing of our attention onto the ostensible subject matter we try to protect ourselves from the deep ego-shattering experience of art.

Traditional metaphysics from Plato on suggests that our perception of the world is rooted in a formal subject/object relationship: that we, as perceiving subjects, are faced with a world of perceived objects; if we read it that way, Foreman’s subjects (by which I assume he means plot, character, dialogue) are actually those theatrical elements that are perceived by the audience member. They are indeed objects (and we all know what that means in Foreman’s universe). And most theatrical experience is based on this distinction.

The object par excellence in the theater is the speaking human body, of course, and it relates philosophically speaking to our own somewhat schizophrenic status in the world. Hopping onto my Schopenhauerian/Kantian high horse again, I observe that the individual human being perceives existence in two ways. First is through that so-called status as subject, or perceiver; second, though, is through that thing we all share in this world, embodiment; the body then is indeed the object par excellence, for it is the only way that we can perceive ourselves in a way which resembles the way in which others perceive us. However, as objects par excellence, the individual subject is privileged in knowing his own object in a unique way: in the ability to sense, to experience, the Kantian thing-in-itself (what Schopenhauer called the will) operating through this body.

Foreman is right to locate the aesthetic experience in presence rather than subject matter, that is in the perceiver’s experience of the object rather than the perceived object itself. What is interesting to me is in how this relates specifically to the theatrical experience of the body: the body of the actor, but also the body of the individual audience member, or the perceiver. And in a way this ties in to Grotowski’s insistence on the selfless actor.

One of the aims in Grotowski’s project is to train the actor to use his body selflessly, that is, to discipline his technique to the extent that this Kantian thing-in-itself, this will, has free access to it. In this way, the body isn’t used as self-expression but as will-expression, as ideal expression. The actor then presents, as it were, an exemplar of sacred being: an example for the audience to contemplate, and to recognize the possibility of this self-negation as a cathartic, healing process. In this is true sympathy with the audience: that the actor presents a possibility as a bodied individual that is open to every single member of that audience individually. (And if we can do this, it is suggested, we can extend this sympathy to other objects in the world, both human and otherwise.) In short: to present the truth, the existence of the unconscious will, which is in itself utterly unknowable (though it can be sensed), through the presence of the body, the self-conscious ego as eradicated as it can possibly be. (This is one deep sense in which the idea of losing yourself in the character is especially resonant.)

If this kind of theater sounds cold, academic, passionless, I assure you that it is not. Because it emerges from the deepest wellspring of human experience, the bodied experience, it is on the contrary warm, accessible, passionate. And it must be so, for two reasons: suffering and sex, Thanatos and Eros.

Whether you call it God, or nature, or the lifeforce (I call it the will, along with Schopenhauer), our bodies are vehicles for the Thing-in-itself, vehicles which share two essential qualities: the capacity for suffering and the capacity for reproduction, and this is why the two classes of the exemplary human being, the saint and the artist, come closest to giving us symbols of redemption. Both attempt, through eradicating the self, to ameliorate suffering, one through asceticism and the other through creation or sensuality, creation and sensuality that lead not to the replication of the race (and therefore the increase of suffering) but instead to a recognition of its tragic situation. The true subject matter of theater is the communication and communion of the perceiving subject and the perceived object through contemplation of that object par excellance they both share, the body.

Where does the playwright come in all this in this Grotowskian, Foremanesque theater? As I mentioned above, the speaking human body is the essential element of the theater, as the moving human body is that of dance, the sound-making human body (through its extension into musical instruments) is that of music. Unique to the form is its utilization of humanity’s capacity to form symbol-making, complex linguistic constructs, and to use these as a means, through the actor, of bodily expression. These texts have the same form as the musical score, and the same limitations: they exist as marks on a piece of paper until fulfilled by the actor’s or the musician’s creative contribution.

I’m trying, at the moment, to consider the craft of playwriting contemplated by the Grotowskian or Foremanesque project of theater, and I’ve come to no firm conclusions, except that as playwrights we have to train ourselves as the actor trains himself or herself: to work to minimize, discipline or eliminate that self so that this will, as a linguistic construct, can emerge through the work. This does not lead to a concept of anything like automatic or extemporaneous writing as a text for the theater. Instead, it leads to the need to allow those complex linguistic constructs, as we’ve experienced them through our interactions with myth, character and narrative ourselves, free and unfettered rein through our own personal experience and consciousness; by discipline I mean the ability to strip away everything that is linguistically extraneous to our expression of the will as reflected through myth, character and narrative, as the performer him or herself struggles against all the blocks and restraints that prevent a full bodily expression of that will.

This differs from the strictly literary project of poetry or prose in that it presents an opportunity for the playwright to further eradicate that self and to enter into a new relationship with the performer and the audience: a new sympathetic, cathartic, collaborative relationship: it is a way of coming out of our hidey-holes and into the world again.

In Praise of an Elitist Art [2006]

In Richard Foreman’s Notes on Zomboid, he makes the case for an elitist art which is not necessarily a coterie art, elitist in its conceptual project, not in its political one. Writes Foreman:

I REALIZED THAT I BELIEVE, THAT NOW IS THE TIME FOR A CELEBRATION OF ELITIST ART!

Let’s dare proclaim that in the face of a society increasingly crying for a media-driven, market-oriented, popular art, reaching out to everyone at once while deep thoughts are officially allowed in such art, they must only come in a form that is easily communicable to all.

BUT I MAINTAIN

that to feed the individual human spirit, the true art of these times must be a kind of demanding gymnasium where sensibilities get rigorous exercise so that those sensibilities then become more refined, able to pick up on and appreciate the patterned intricacies of a world which is usually, in art, simplified into recognizable social and psychological clichés or knock-out effect. Such normal strategies lie about the world because they talk about what we already know (which is always wrong) in languages with which we are already familiar (and therefore put our more delicate mental mechanisms to sleep) all this, instead of waking us up with the uncharted energies that throb behind the facade of the shared world of communicable convention.

There is a distinction here about the wisdom of communication as communication whether it’s doing us any good to think about communication when we’re not thinking about what it is we’re communicating, or whether the vehicles we use for this communication (especially language) are reliable, or whether we’re even driving these vehicles for communication properly.

As I understand Lacan, language itself is a piss-poor car. The unconscious may be structured like a language, but it is not at all the same thing as a language, and so far as this goes for the stage, Grotowski’s efforts to develop an embodied visual language must partake of this same ambivalent status. It is, then, in the way most of us conceive of language as somehow reliable that we’re engaging in a fool’s errand.

Why elitist, though? Because Foreman’s project and admission of quotidian language’s failure to communicate what we need for redemption rather than what we want requires a revolutionary, radical break with what we might call a collective consciousness. Ironically, our urge as human beings is to reach beyond this collective consciousness and recognize ourselves as capable of more penetrating perceptions. The collective consciousness itself drags us back into its prison of convention; it sets up taboos and makes a crime of any perception or definition or experience not easily digestible in its own meaning-making intestinal tract.

Elitist does not mean wealth. Elitist means that this is art for each of us individually (which is where aesthetic experience inheres, whether in a gallery or in a 3,000-seat theater), not for the health of the collective consciousness. Foreman again:

SO IN TODAY’S ARENA, I MAINTAIN THAT ONLY ELITIST ART

presents the true facts of always-in-process human beings who, while pretending to themselves and others that they are coherent wholes are really but a tissue of micro-tendencies and impulses, most of which are effectively ignored by the defense mechanism of consciousness that allows the individual to feel secure in his or her picture of the world.

BUT ELITIST ART

Offers the spectator a chance, through the development of subtle discriminations, to enter the true PARADOX of lucid, aesthetic sensibility.

ELITIST ART

trumps the popular art of media culture, offering the alternative to the bottom-line world that leaves so many of us parched, spiritually depleted, half human precisely because we are asked

TO DENY OUR ELITIST TENDENCIES!

The experience is available to anyone who wants it: Anybody is welcome to enjoy elitist art, Foreman continues. It tends to speak of powerful hidden things and energies, in language (the full range of theatrical language) that is isomorphic with those hidden things and energies, rather than in the language of daily life because a language made isomorphic with such intuited processes seems most connected to ultimate, deep-lying things. I’m afraid, though, that this experience is not going to be available to those who want to be entertained through traditional, conventional methods, or amused through picking through the shinier objects flowing through the spiritually dead but still pulsating intestinal tract of the everyday collective consciousness, especially as we drag that consciousness into our private selves and construct ourselves through its continually simplifying assumptions. The jokes may be harder to get (though once we get them funnier for all that). It will be harder to situate ourselves in the theatrical experience, but once situated there, we will, in fact, see more of the stage that constitutes both our aesthetic experience and the world which is represented to us through our own unreliable consciousness.

More, we will be able to play in language, seeing it as a place for the dynamism of self, rather than an avenue to closed-off cul-de-sacs of conventional meaning as defined for us by genre, by mass media, by our own imprisoning closed-mindedness. And we will be able to play in our livesthat serious play in which children engage as they figure out how this fragmented body, how this fragmented world, how this fragmented perception works. We will see other possibilities than that which socially-defined language presents for us.

Some will no doubt be worried by the riskiness of the venture. They will no doubt ask what the risk is; Foreman says it is this:

To risk offering an art based on this split is to walk the tightrope over the abyss between imagined human mastery and the un-chartable other [that frightening Lacanian “Other” that is located in our own absorption of and definition in language, our own desires that we seek to understand] that is never controllable or knowable.

BALANCING PRECARIOUSLY

in that energized limbo where the art called difficult does its secret and unpredictable work.

And that word difficult is only in quotes because our collective consciousness puts those quotation marks around it, trapping it in a place that can safely be ignored or dismissed by those of us who wish to continue our sojourn in the darkness.

Zomboid! [2006]

There must be something wrong with a face that’s always the same face.

In Zomboid!, which Richard Foreman bills as his Film/Performance Project #1, the playwright/director tries to come to terms with the projected moving image, especially as it affects his very stage-bound meditations on perception, and he seems to have hit on a new physiological solution. The window downstage right, the window from Maria del Boscos atelier, is back, a hole in the wall that allows the world’s light to stream in as the world’s light streams into the eye. Now, though, this seen world is reflected back to the audience and into the interior of Zomboid!s world itself: a seen world of upper-middle-class interiors and individuals, a world, seen from the chaotic arena of the interior, which might indeed be upside-down: video projection as a digital retina. It’s this world which the individuals of the play need to contend with and interpret now, and as that #1 in the subtitle of the production indicates, this interpretation requires yet another new start.

To begin the process, one liberates the formerly functional aspects of perception, and for Foreman that means letting go of the need to control those aspects: in his theater, the dwarves, the supernumeraries who in past Foreman productions have been largely responsible for set changes and choral interludes. Several members of the Zomboid! cast were dwarves in previous Foreman productions. They have been let loose here, to be given their own chance to learn to see as individuals.

There’s nothing obscure about the objects scattered on the stage at the beginning of the show: large eyeballs and alphabet blocks introduce the thematic concerns of Zomboid!. The two other objects with which the characters need to contend during the show are the blindfold and the donkey, a beast of burden. Fortunately, the Girl in the Beret (Temple Crocker), who is making the effort to find a purchase for herself in this world, is assisted by three other women and a tall man, who demonstrate for her the ways in which both the blindfold and the donkey can be manipulated to her own interpretive ends. The blindfold is an indication of sexual and perceptive vulnerability, but in this vulnerability is potential interpretive power: the possibility of seeing the world anew; after all, under a blindfold the eyes don’t cease to function, and she indeed sees something; what each of us sees when blindfolded will be different for each of us, a play of color, an imagining of the world we can’t see and over which, therefore, we have full interpretive range.

Most of the comedy of Zomboid! appears in the guise of the poor stuffed donkeys, which provide multiple prods to interpretation. As a metaphor for our own human bodies, the donkey is certainly a burdensome if inescapable part of our perceptions: poorly conceived vehicles for racing (both the human race and the rat race), but also, in one of the coarser jokes of the production, a vehicle for sex, for our personifications of Eros. Whether we saddle up our donkeys or the donkeys saddle up us is a central question in Zomboid!. The beret-girl’s teachers counsel recognition, integration and play, which may be the wisest choice.

In freeing his dwarves to interpret this world, Foreman seems to be striking out on a new humanistic road following the pessimism of last year’s elegaic The Gods Are Pounding My Head! As if he reached the end of a road with that production, he and his theater needed to begin again, and though only a few of his former design and aesthetic approaches have been abandoned, the addition of video has introduced a new exterior world into this perceiver’s world: it suggests a new attempt to come to terms with the social world outside the theater, a newly-recognized antagonism, and a suggestion that liberation from externally-constructed realities is still possible if only we, as perceivers, learned to begin again as well.

For the play ends on a note of a new beginning. Perceptually illiterate at the start, the Girl in the Beret (and Temple Crocker’s performance is terrific, a Maria del Bosco set free from her name and social identity) learns through the process not to see the world through Foreman’s eyes, but through her own as she, a contemporary version of Vermeer’s A Girl Reading a Letter by an Open Window, sits at the hole to the world, looking out, examining with confidence her own communication to herself in the light of the world, as earlier she had learned to write, to make her own symbols, with confidence and considerable beauty. (The reference to Vermeer is no mistake: the 17th-century Dutch painter’s bright, unique lead-tin yellow is also used in several of the costumes worn in the video.) It’s an unusually peaceful, emotionally moving moment: an image of serene empowerment.

Zomboid!, I’m glad to say, is also a daringly sexy show, not least because of those blindfolds and Oana Botez-Ban’s costumes. Because this is one of Foreman’s most technically complex productions in several years, credit is also due to technical director/lighting engineer Paul DiPietro, lighting engineer Joshua Briggs and video engineer Vivian Wenli Lin.

NOTE: I don’t know whether this is Foreman’s best show or not, but I was certainly moved by it, as I was by Panic!, a sentimental favorite. It shouldn’t be necessary to say, but: everything I’ve written above is applicable only to myself. Foreman’s perspective on what’s going on, Temple Crocker’s, yours, is going to be quite different. My interpretation blindfolds me; you shouldn’t allow it to blindfold you as well. You’ve been warned.

Wake Up Mr. Sleepy! Your Unconscious Mind Is Dead! (2007)

If happiness enfolded human beings, then human beings would find it difficult to improve themselves.

The invention of the airplane, a mortal blow to the unconscious, a deep voice says at the beginning of Richard Foreman’s Wake Up Mr. Sleepy! Your Unconscious Mind Is Dead!, his 2007 extravaganza. And despite this characteristically dour observation, Mr. Sleepy is one of Foreman’s most cheerful, optimistic plays in years. As the technology of flight (and perhaps technology in general) robbed the 20th century of a dream of flight by making it physically possible, a dream fulfilled but unsatisfying in its fulfillment, the century has had to recover the dream of flight, and perhaps dreaming itself, amidst a technology of images that threatened to render dreaming and the unconscious itself superfluous.

No wonder Foreman was driven to integrate the video and film image (the dream) into his stage work (the world), beginning with last year’s Zomboid!, which was to many spectators an unsatisfying marriage: but first steps, baby steps, are ever tentative. This self-created technology is a minefield, and we’re unprepared to negotiate it (as adults, our feet are awfully big and we’re not as dextrous as we used to be). In Mr. Sleepy, an aviator (James Peterson) attempts to manipulate those remaining on the ground (Joel Israel, Chris Mirto, Stefanie Neukirch and Stephanie Silver) in this landscape newly shorn of the ability to dream, and he fails more often than he succeeds. The girls, somehow, manage to regain this ability first (perhaps it’s the sensual fertility of women, of which we’re reminded by the babies and their worn stuffed animals on stage and often in their own hands), but it’s not gender that’s important: it’s the ability to see anew, to waken what technology (or, rather, our submission to technology, since technology has no conscious will of its own) has put to sleep; to tear the newspapers (filled with useless information gathered from around the globe) wrapped around our heads to see what lies beyond them. To regain a childlike wonder, we need to become as children again.

Or we risk missing the point. Foreman’s plays are completely devoid of subtext; they’re all surface, there’s nothing to figure out. Ok, ok, are there any young children in the audience tonight? a deep voice asks 23 seconds into the play. If there were young children here tonight I would now be explaining to them specifically. Everything here is just for you. These are such shallow thoughts that even boys and girls can understand them without trying; the play contains its explanation within itself, it’s not a puzzle. The unhappy adults of the play, the languid actors and actresses of the video presentation (filmed in collaboration with The Bridge Project at Lisbon, Portugal’s Miguel Bombarda Hospital, a retreat for the sick and injured) grouse and complain about their situation: Maybe it could happen in my lifetime, tick tock, tick tock; it’s broken and it can’t be fixed, they repeat to themselves, having given up. The unhappy children left on the ground are fearful and anxious, and much of the first half of the play is spent in seeming flight (pun intended) from the airplane that hovers above. Finally, a girl in a pantsuit begins to climb a wall and finds that, without technology, through a movement and placement of the body, a new perspective on the world can be recaptured. It’s a hint that dreaming is possible again.

Midway through the play, the adults on screen are impelled toward hope as an escape from their unhappiness: Maybe it could happen in my lifetime, an on-screen character says. The deep voice provides, with hindsight, the antecedent to this it with an instruction to the children onstage and in the audience: When the unconscious is dead the fighter airplanes say we are alone on earth, we are blind, we are deaf, with no tactile sensation. (If it is broken, if it is broken.) When the unconscious is dead please use the human mind to dig up from the depths that mental baffle machine, uncovering the sleepy giant whose name must never be spoken. (Never spoken.) So all right, a reach for that Judaic G-d. But we left that personal god behind generations ago: the sleepy giant of our unconscious begins to be personated in ourselves. On screen and on stage the human body’s sensuousness begins to be explored: a woman’s bare leg is slowly caressed, the woman’s face, turned toward the audience, begins to register a subtle pleasure. The world can even learn from the dream: a woman rubs her belly, slowly and thoughtfully, on screen; a girl (Stefanie Neukirch) before us imitates her action, a soothing, calming gesture that wakens the body and the unconscious alike.

Foreman’s brand of political and cultural didacticism is crystal clear in Mr. Sleepy; you can’t really get more obvious (as I said before, no subtext). Remember, things bite back. Risk it, the voice implores. If there were young children here tonight, I would now be explaining to them specifically that once upon a time a lonely man cried out. The voice finds, in a memory of childhood (the voice’s childhood, one would never assume that the voice is Foreman’s because the assumption is not necessary all surface, remember), a means of negotiating technology to find human connection again:

Guess what it really happened to me when I was a kid. I was a young person dreaming and I climbed out of a pit in this dream, a pit dug into the earth, and as I climbed out of the pit, and looked over the edge of the pit, there over my head was an airplane flying low, and in that airplane were people, people looking at me, people jammed into the cockpit looking at me, and from their eyes, from their eyes into my body.

This could be an intense glare of belonging, of love. (And hence a woman’s voice [the voice of Foreman’s partner, Kate Manheim, who returns in recorded presence after some years of absence from Foreman’s plays]: no distinction is made between ideas that are good for you, and ideas that are bad for you.)

One needs to be a young child again, a boy or a girl, to make a new beginning beyond the cultural moralisms dictated by ideas of good for you and bad for you. An Eden is recaptured; as one of the screen legends has it at the very end of the play, these are THINGS HIDDEN SINCE THE BEGINNING OF THE WORLD that is, our beginning, the world into which we are thrust at birth. Theodor Adorno, at the end of his life, posited all of his own work as an attempt to recapture his childhood, and through it, the primal source of our origin. This means recognizing the world, and all the things in it, as having emerged from that same origin: technology the human-built screen to blind us to it. Ironically, all we need do to recapture the unconscious is to see the conscious world true. If all this seems too much to handle, Foreman holds our hand in a program note:

RELAX! Do not work overly hard trying to understand. Know instead it’s about the elusive Unconscious Mind. Surfacing and re-surfacing (as in music). Just stay alert and notice everything that arises and asks to be noticed.

As usual in Foreman’s plays, there are beautiful sequences, the most beautiful here being the rejection of the suicidal impulse when it all becomes a little too much; just as the girls prepare to slit their wrists with a pair of long knives, they make the decision, instead, to live, even with the pain that this rediscovered unconscious brings them; they drape their white delicate blindfolds over the knifepoints that threatened their very lives.

Not to put too fine a point on it (and to bring in a little irrelevant biographical gossip), Foreman might have, at the beginning of his 70th year in this technology-strewn world, rediscovered in his revised aesthetic a new means of coping with a world that, through mankind’s use of technology as a blinker to possibility, has had airplanes flying around it since his birth. Might he, at 70, have rediscovered his love for it, and found a means of communicating the possibility of this love to his audience (if they can make themselves as childlike as well)? As Proust knew, too, in every attempt to recapture childhood is the attempt to recapture Eden, to see and be seen as intensely innocent boys and girls, and the world opens to perceptive possibility again.

The Manifestos and Essays by Richard Foreman (2014)

Novelist, filmmaker, and raconteur Richard Foreman is best known for his theatre work as playwright, designer, and director — but even here, one must be careful to distinguish Foreman’s more “commercial” projects (from his musicals with Stanley Silverman to his opera and “straight” theatre work) from the plays he’s been producing over nearly 50 years through his Ontological-Hysteric Theatre, founded in 1968; the most recent OHT production, Old-Fashioned Prostitutes, ran at the Public Theater only last year [in 2013].

Foreman’s influence has often been cited as a central ingredient of contemporary drama and theatre, but this influence may be more through his example than his specific techniques and work. Since 1968, Foreman’s OHT plays have been uncompromising investigations into the nature of his own vision and consciousness; while the Incubator Arts Project, which now occupies the space at St. Mark’s Church once occupied by the OHT, was a project undertaken with Foreman’s blessing, most of the work produced there doesn’t resemble Foreman’s. [NOTE: The Incubator Arts Project closed several years ago.] Foreman’s spirit emerges in the courage that he engenders and recommends in these theatre artists to be uncompromising in investigating their own visions, not his.

While Foreman’s theatrical productivity has tapered off somewhat in the past few years, and the OHT productions have become more rare, we are fortunate now to have The Manifestos and Essays, a new collection from Theatre Communications Group that gathers Foreman’s theoretical writings, many of which are hard to come by, into a new, convenient, single volume. The contents span from the three “Ontological-Hysteric Manifestos” written in the 1970s, to more personal essays from the 1980s and 1990s, to two interviews conducted with Foreman in 2008 and 2009, and finally 40 pages of notes that relate to his film Once Every Day, which ran at the New York and Berlin Film Festivals.

Central to Foreman’s theatre and film through this entire period is the nature of consciousness itself: that new ways of seeing the world can lead to new ways of acting within it and contemplating it, that in our daily lives we remain immune to the underlying dynamics of our experience as a body and object in a world against which other bodies and objects continue to press. Foreman, a Barnumesque showman, often finds these dynamics erotic and comic, though more often than not one is left with a note of melancholy as the difficulty and (for some of us) the impossibility of rearranging our consciousness becomes more and more evident. His spare early productions, sometimes three hours in length, gave way to a more baroque sensibility as his designs became more crowded (the more objects, after all, the more there is to investigate) and more frenetic (as our own perceptions have become more fragmented and hysterical, one following and seizing upon another in an unending spiral that leads to chaos).

That said, there is a progression in Foreman’s career from those early, near-minimal productions to a more carnivalesque phase, then more contemplative in plays like The Cure and The Mind King, then more controlled with his plays of the early 21st century. Surprisingly for a body of work which foregrounds abstraction, they are all products of their time, as all plays and works of art are, on some level, products of their time. Symphony of Rats and King Cowboy Rufus Rules the Universe both have explicitly political themes, but the questioning of the ideology of consciousness in 20th century America obviously has an implicit political dimension as well. To stop, to think, to contemplate, within a culture growing more and more transparent and anxious — these may be the most politically (and, obviously, aesthetically and culturally) radical actions in a society seemingly in love with its own rapid, fearful, frantic movements.

The manifestos and essays in the TCG volume detail the frustration and dissatisfaction Foreman experienced in the theatre of the 1960s, even the theatre of other avant-garde theatremakers, and mark out the intellectual basis for the OHT. The plays themselves, of course, emerge more from Foreman’s instinct as a theatremaker and writer than from any body of philosophy he may or may not have come across. Like many other artists similarly well-read and seemingly over-intellectual, Foreman seems to pick and choose, denying that he “understands” some of the more abstruse structures of thought. Instead, he’s a packrat — he takes from those structures what he chooses, what is useful to him in his own thinking about his work.

Foreman recommends a similar approach to his own theoretical writings, introducing the “Film Notes” to this volume:

WHAT FOLLOWS IS NOT TO BE READ STRAIGHT THROUGH. PERHAPS NOT TO BE “READ” EXACTLY — BUT OCCASIONALLY “DIPPED INTO” WHEN ONE (MYSELF) FEELS BLOCKED AND EMPTY: BRIEF ENCOUNTERS TO RE-FRAME THAT EMPTINESS AS A MEANS TO …