Reflecting the increasingly Austria-centric concentration of this journal, I posted items this week about the late Professor Marjorie Perloff and the holiday offerings of radio klassik Stephansdom.

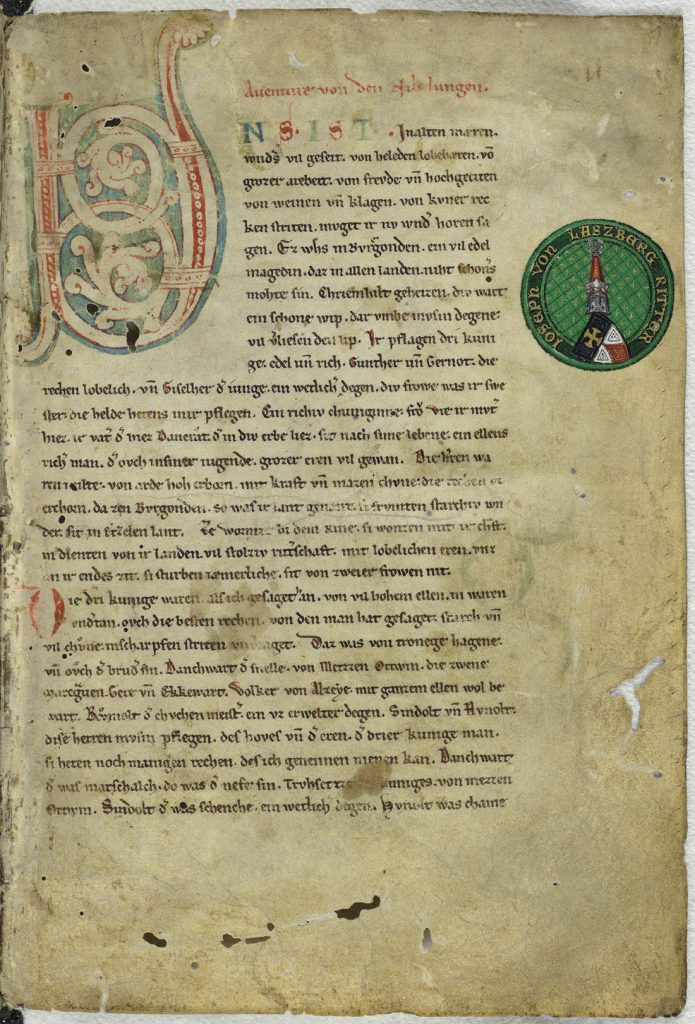

In addition, I raise my glass today to the Nibelungenlied; as part of my continuing education and immersion in all things German and Central European, I’m reading the Penguin Classics translation by A.T. Hatto, a rather interesting fellow himself. A page of the manuscript, from a 13th century codex, is above. I’m just past the midpoint now, as Kriemhild stopped at Melk and then proceeded to Vienna for her marriage to Hungary’s King Etzel. As it happens my family and I were in both Melk and Vienna just a few months ago; no sign of Kriemhild, but that was some time ago.

Compared to the much older epics of the Mediterranean Sea — the Iliad and the Odyssey for starters — the Nibelungenlied is far sparer and relatively god- and goddess-free, with more of an emphasis on the internal lives of its characters; apart from Siegfried’s cloak of invisibility, there’s very little supernatural about it. I suppose you could say that, like the climate from which it emerged, it’s much colder than Homer’s poems, but I rather like that; although of course there’s considerably more Christian and chivalrous material, there’s also an awareness that paganism was still an element in social, cultural, and religious life (indeed, a Christian Kriemhild marries a pagan Etzel, a point made by the anonymous Nibelungenlied poet). In addition, both Brunhilde and Kriemhild possess much more agency and are far more energetic than Homer’s female characters — the Nibelungenlied is much sexier and erotic, for want of better words, than the earlier epics. Wagner’s Ring operas have a rather scant resemblance to this poem, relying more on the Volsung Saga, but the Nibelungenlied itself is still quite a wonderful read.

Reading the rest of it is how I’ll be spending much of this weekend.