I’m not much for social media but I still maintain a Facebook account, primarily to announce new posts from this journal, and this morning I was glad to do so. Marion Eigl, the morning host on radio klassik Stephansdom, walked us through her arrival at the station in the wee small hours of the day — just as the sun is rising above the Stephansdom, in the shadow of which the station broadcasts — and it reminded me of just how beautiful the city is in those very early daylight hours, when the streets are nearly deserted and the sky brightens through a series of glorious blues. One of the great pleasures of listening to the radio is the knowledge that, at the other end of the connection, there’s another human being sharing in the music with you from the broadcast booth, something that isn’t the case with streaming music services. So guten morgen, Marion. The city looks lovely at that time of day.

I’m not much for social media but I still maintain a Facebook account, primarily to announce new posts from this journal, and this morning I was glad to do so. Marion Eigl, the morning host on radio klassik Stephansdom, walked us through her arrival at the station in the wee small hours of the day — just as the sun is rising above the Stephansdom, in the shadow of which the station broadcasts — and it reminded me of just how beautiful the city is in those very early daylight hours, when the streets are nearly deserted and the sky brightens through a series of glorious blues. One of the great pleasures of listening to the radio is the knowledge that, at the other end of the connection, there’s another human being sharing in the music with you from the broadcast booth, something that isn’t the case with streaming music services. So guten morgen, Marion. The city looks lovely at that time of day.

The programming at rkS also caters to my increasingly eccentric taste in music (though I should also mention here that rkS broadcasts high mass at the Stephansdom a few times a week, which also caters to my increasing eccentricity). When I was younger I used to enjoy orchestral music much more, but now, at 62, I’m drawn more to vocal and chamber music, especially medieval and renaissance composers like Hildegard von Bingen and Heinrich Schütz, then skipping over a few centuries to the Second Viennese School, with a brief but significant sidetrack to the classical era of Mozart and Beethoven. There is a spiritual aspect to this as well, which may also be tied to aging. As we get older, it is said, we grow more into our more mature selves. My mature self finds more affinity in this music than it used to. Don’t get me wrong — I’m as prone to slip on an album by Frank Sinatra or Elvis Presley as the next Joe, when the time seems right. Still, it seems to be that the music of hundreds of years ago pleases my ear and my meditations more than most.

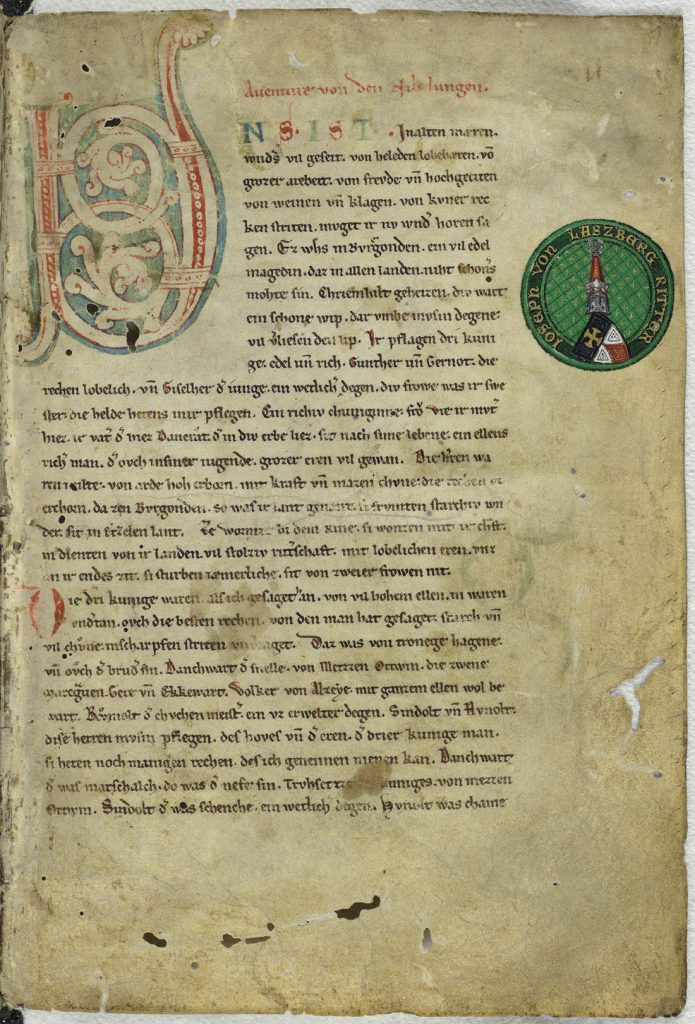

The geographical basis of these meditations is more centered in Vienna and environs than anywhere else. There is something about the Danube, I suppose, and Central Europe as I’ve mentioned here before was after all the original home of my ancestors. My recent listening is paralleled by my recent reading, too — the contemporaneous Nibelungenlied and Hildegard again, and the literature of Musil, Doderer, and Kraus, all writers contemporaneous with Schönberg, Webern, and Berg. The spiritual center of all this work seems to be the Austrian capital, itself an architectural museum with exhibits spanning from Fischer von Erlach to Adolf Loos. I don’t believe that I’ll ever be able to spend an extended amount of time there to probe these meditations in situ, as it were. But I will make do with what I have, even as I continue my studies in the German language; as Wittgenstein once said, “The limits of my language mean the limits of my world,” and fortunately I can still broaden those limits and maybe broaden my meditations through an assiduous attention to my language lessons.

At the moment, I’m turning my attention to radio klassik Stephansdom, though — right now host Eva Reinold is treating me to a few Beethoven bagatelles, and I think I’ll have a listen to those. I do want to note that rkS is continuing its fundraising drive, and if rkS suits your streaming fancy you should make a donation here. And turn up the volume.

I’m not much for social media but I still maintain a Facebook account, primarily to announce new posts from this journal, and this morning I was glad to do so.

I’m not much for social media but I still maintain a Facebook account, primarily to announce new posts from this journal, and this morning I was glad to do so.