A few weeks ago I returned from my first visit to Vienna in about 15 years, and I returned feeling my connection with Eastern Europe more strongly than ever. (For the sake of argument, and I admit it’s arguable, I’ll posit the Rhine as the division point between Eastern and Western Europe; once one admits a Central Europe, things get even thornier.) Of course I was born in the United States, as were both my parents, but for generations before that, my ancestors were Eastern European — which may explain my comfort there and my discomfort here. I can’t call Eastern Europe home — home is where my family is, and they are here. But my affinity is for that culture more than for this one. As Timothy Garton Ash wrote, and whom I quoted in the short essay below:

Our identities are given but also made. We can’t choose our parents, but we can choose who we become. “Basically I’m Chinese,” Franz Kafka wrote in a postcard to his fiancée. If I say “basically I’m a central European” I’m not literally claiming descent from the central European Yiddish writer [Scholem] Asch, but declaring an elective affinity.

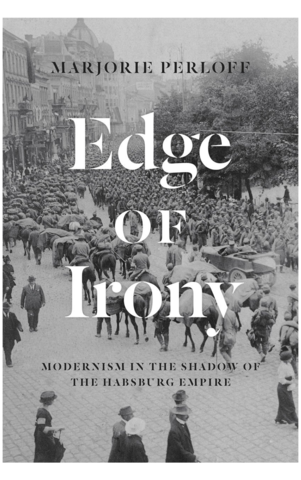

There are a few ways to declare that affinity; for example, I return from Austria more determined than before to enter the world of the German language more fully, and I’m taking lessons to that end. I’ve fired up Radio Klassik Stephansdom regularly since my return. And I’m revisiting the writers that Marjorie Perloff explored in her fine book Edge of Irony.

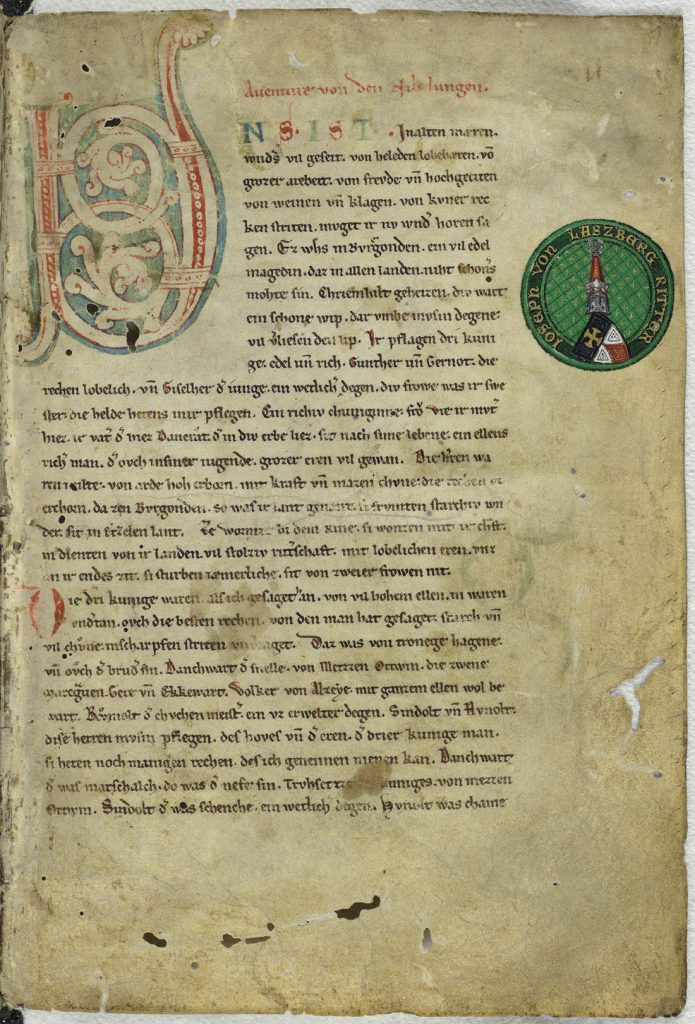

In a BBC documentary of a few years ago, historian Simon Sebag Montefiore called Vienna “the capital of the empire of the mind,” noting its location as the easternmost point of the West, first built as a military outpost to defend against barbarian attacks from the East. If we admit Germany to our definition of Eastern Europe, we find the highest achievements of the human spirit born in these lands: in architecture and design, the Stephansdom itself to the Wiener Werkstätte; in philosophy from Kant and Schopenhauer to Kraus and Wittgenstein; in literature from the printing press and the Nibelungenlied and Goethe to Musil and Paul Celan; in music from Bach and Beethoven to Schönberg; in science from Kepler and Leibniz to Freud and Einstein. We also find perhaps the height of discerning elegance and civility (not to mention a lively eros!). And even as Eastern European thinking and culture reached its apogee in the early twentieth century, it all came crashing down in a hysterical, militaristic, nationalism-fueled, and antisemitic apocalypse in the years between 1914 and 1945 that still beggars rational explanation, proof if any were needed that civilization is a very thin veneer. It’s getting thinner all the time. Nonetheless, it is this part of the world where my own affinities lie (you couldn’t pay me, for example, to set foot in the Middle East).

This is all to follow up, I suppose, with what I wrote back in June 2023, and which is reposted below.

The verdict is in. According to 23andme, “[my] DNA suggests that 98.1% of [my] ancestry is Eastern European.” The 23andme findings more specifically identify “places where you have DNA in common with more people who report ancestry from that particular region.” The specific regions are identified from “highly likely” to “possible match”; for me, Lithuania and Poland are “highly likely” matches; the Czech Republic (specifically Prague), Ukraine, and Russia “likely” matches; and Hungary and Slovakia “possible.” This more or less coincides with what I already knew for certain about my family’s background: on my father’s side Ukrainian and Slovak, on my mother’s Lithuanian and Polish. There were no real surprises. The remaining 1.9% of my ancestry appears to be comprised of Scandanavian (0.7%), Ashkenazi Jewish (0.2%), and somewhat amusingly Chinese (0.7%, which may explain my delight in spicy Szechwan cooking) fore-fathers and -mothers.

Of course, these identifications are based on present-day national borders — geopolitical fictions, as the history of the region proves over and over again. When my father’s father emigrated from Europe in 1914, he emigrated not from Ukraine, which did not then exist as a state, but from the state of Austria, which was where the town of Ternopil was located before World War I. Similarly, the borders of both Poland and Lithuania shifted almost maniacally through the twentieth century, not to mention the centuries before. The only thing that is most certain is that my family’s origins, from the Baltics to the Black Sea, were located in the Bloodlands: Timothy Snyder’s name for the region most heavily devastated by the twentieth century’s Thirty Years’ War between 1914 and 1945.

Born in 1962, I am a second-generation American: for the dozens of generations before that, my family was Eastern European. As I’ve tried to piece together my more recent familial genealogy, I’ve found too many voids in the record to be more certain than this. But my cultural genealogy — ah, that’s a different matter. In his excellent new book Homelands: A Personal History of Europe, Timothy Garton Ash notes: “Our identities are given but also made. We can’t choose our parents, but we can choose who we become. ‘Basically I’m Chinese,’ Franz Kafka wrote in a postcard to his fiancée. If I say ‘basically I’m a central European’ I’m not literally claiming descent from the central European Yiddish writer [Scholem] Asch, but declaring an elective affinity.” The similarities in their names — Asch and Ash — aside, there is that which draws Ash to the region not via intellect or emotion exclusively, but via a sympathetic temperament and disposition (I wrote a little about mine here) that combines these two characteristics with others. When I first visited the region in 1990 on a whirlwind six-week tour through Austria, Germany, Hungary, and what was then Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia (those pesky borders again), I had an uncanny feeling of comfort, of belonging. My Jewish friends have described to me a similar feeling when they first travel to Israel, and I imagine it’s much the same. It feels like home.

It certainly did so when in August of 1990 I joined thousands of others for a Rolling Stones concert in Prague. As Czech journalist and musician Ondřej Hejma, who was also there somewhere in the crowd near me, described it:

This was a confirmation that we are entering the world of free market, democracy, and free speech, and that we will see it with our own eyes. And that’s exactly what happened. … The [Rolling Stones] concert at Strahov was a social event, a philosophical event and something like a milestone in history.

In his book, Ash also introduces a generational concept that defines age groups according to their formative political experiences in their early adult lives. He defined this in a recent Substack post: “Today’s Europe has been shaped by four key political generations: the 14ers (with their life-changing youthful experience of the first world war), the 39ers (the second world war), the 68ers (1968, in all its different manifestations) and the 89ers (influenced by then Czechoslovakia’s Velvet Revolution and the end of the cold war).” I am myself an 89er, as are two historians whose writing I find sympathetic to my own cares and interests, Anne Applebaum (born 1964) and Timothy Snyder (born 1969). Blessed it was to live in that time, as the saying has it.

And, from the perspective of 2022, perhaps damned as well. The deep hope and life-changing experience that Hejma describes couldn’t last, but one would have hoped that it wouldn’t have deteriorated so rapidly. Even a few years after 1990 I noted a distinct difference in the eastern European zeitgeist when I returned to teach English to high school students in Moravia: the students’ interests turned more to Germany and Austria than to the United States, primarily for economic reasons, and the hostility directed towards the Romani population was palpable even among those Czechs who were otherwise most politically liberal in the Western sense of the word. Americans were not welcomed as warmly has they had been in 1990. Last year, when the Russo-Ukrainian War began, it seemed as if the promise of all those color revolutions had been cruelly dissipated. In Europe there was also Brexit and the immigrant crisis, but here there was Trump and an immigrant crisis too, not to mention an upswing in threats of political violence and to the sanctity of the individual conscience — sexual, religious, racial, cultural. My own two children are likely 22ers, as Ash would define them. I can only wonder what’s next.

There is still a war in Ukraine to be fought and a Presidential election here in the United States next year that threaten to remind us that, as some wag once put it, history may not repeat itself but it does rhyme on occasion. As I recall my experiences in Eastern Europe (as 23andme calls it), and look back with some more atomic attention to my ancestry, I hope not to succumb to nostalgia or sentiment but to shore up those personal ideals that were so profoundly represented in the culture of the 89ers: that of freedom, of validation of the individual conscience, of the right to determine one’s own integrity as countries like Ukraine defend the right of geopolitical self-determination. That it remains clearly an uphill battle is not in dispute. But if I don’t fight that battle, I and my family will clearly lose. Slava Ukraini, and the rest of us, too.

I want to start the month off by recommending Marjorie Perloff’s

I want to start the month off by recommending Marjorie Perloff’s