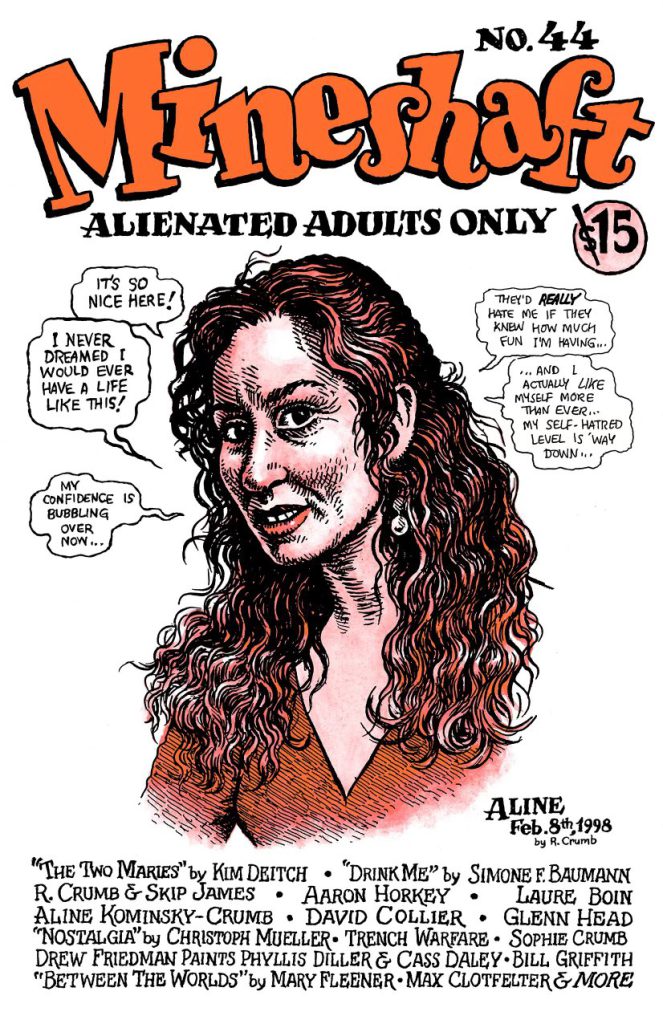

Now available for holiday giving, issue #44 of Mineshaft magazine dropped into my mailbox in a plain brown envelope a few weeks ago, and as usual it’s a magazine to spend a few thoughtful evenings with. (And you can impress your friends when you leave it on your coffee table.) Among the highlights are tributes to the late Aline Kominsky-Crumb and Diane Noomin from Bill Griffith and others; a new, haunting story called “Nostalgia” from Christoph Mueller; Mary Fleener‘s meditative “Between the Worlds” travelogue; a Skip James portrait from R. Crumb; co-editor Everett Rand’s ongoing saga of Mineshaft itself; and great new stuff from Simone Baumann, Glenn Head, Drew Friedman, and company. I wrote a little more descriptively about Mineshaft here.

Mr. Friedman has called Mineshaft “the best magazine being published in the 21st century,” and who am I to argue with Drew Friedman? Certainly it’s one of the few magazines to which I maintain a subscription (the others are Acoustic Guitar and The Syncopated Times, which shows you where my head is at these days). You can yourself join the illustrious Mineshaft community easily enough; the current issue is available here, and you can sign up for a subscription here. And while you’re there, why not give the gift of bemused alienation to someone close to you?

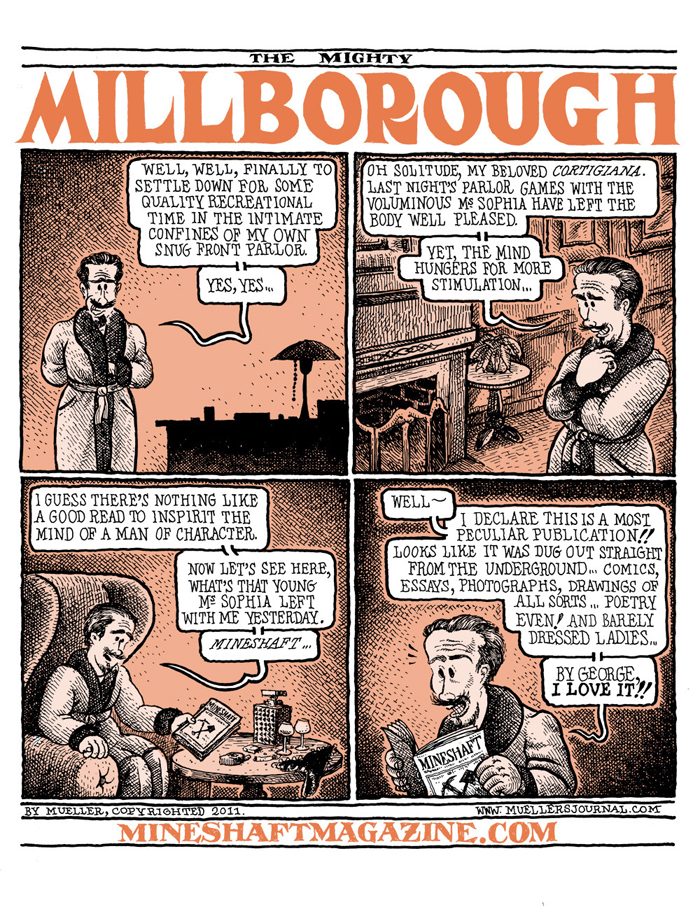

Below, The Mighty Millborough himself discovers Mineshaft, as told to Christoph Mueller in 2011: