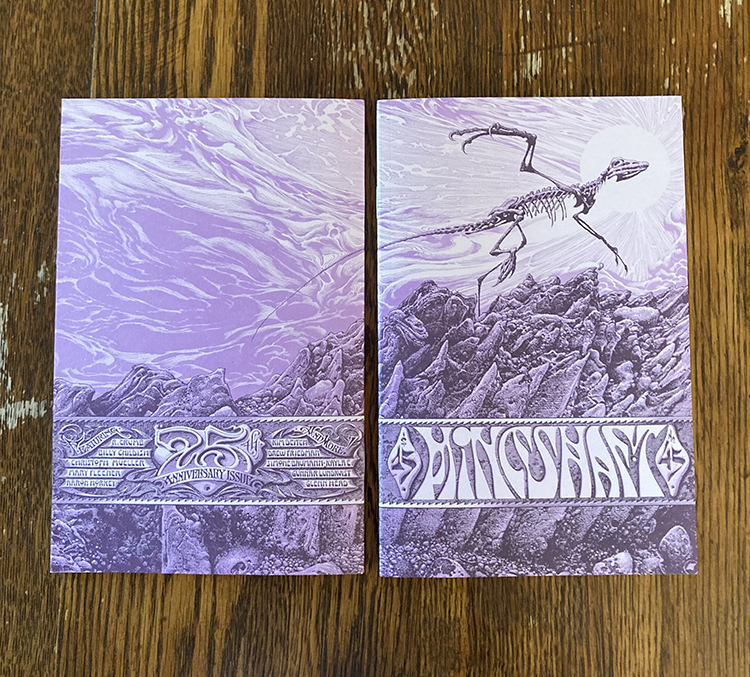

The mailman slipped me the latest issue of Mineshaft #45 last week — the 25th anniversary issue of the magazine that published its first issue back in the last century. I read through just about the whole thing in one sitting, but “read” may not be entirely accurate: each issue is a world in itself of visual and linguistic acrobatics from writers and artists old and new. It seems churlish to pick out just a few highlights, since Mineshaft is best read from first page to last, but in #45 you’ll find:

- First, that splendid, endlessly fascinating wraparound cover by Aaron Horkey

- Simone F. Baumann’s depiction of her very brief career in a hooker bar

- A memoir of pre-teen transvestism by Billy Childish

- Mary Fleener’s comic travelogue through the current state of the humanities in academia

- R. Crumb’s portraits of two great blues masters

- Drew Friedman’s rendering of popular Chaplin imitators

And there’s more, much more, besides.

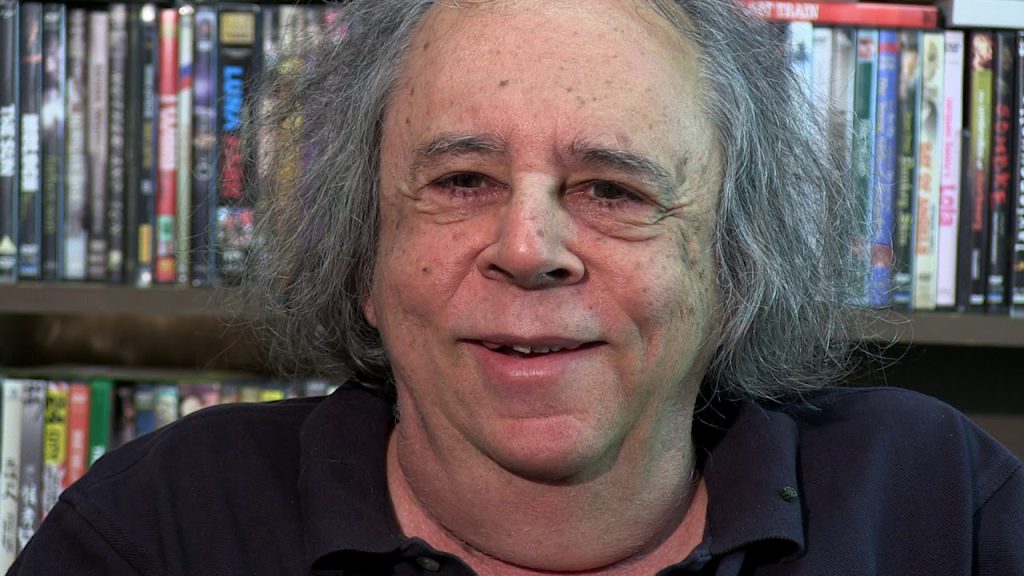

In the sixth part of his continuing saga about life with Mineshaft, publisher/editor Everett Rand muses upon the magazine’s continuing appeal. “[The] magazine is an attempt, by me, to keep control of my world. I’ve always enjoyed the possibility of living in art, rather than always being stuck in real life. That’s what a great painting or book does for me. They give me another world that I can step into and inhabit for a while.” He continues:

My own editorial vision … is always pushing artists and writers to send us their best work, and there’s no money in it. People can resent this, or not have the time for it. … Despite the sacrifice and hardship, I think people come on board because of the community, in order to be a part of the experience. The generosity of the Mineshaft community is really what keeps Mineshaft alive. Everybody comes together to help make something tangible, that is nicely put together, and that otherwise wouldn’t exist. It’s not practical and you have to be a bit of a dreamer and idealist. The readers are a big part of this community too.

It is, it must be said, not a big community. Only 1,350 copies of Mineshaft #45 were printed, but that community is always inviting new members who want to share that world with the contributors, and the community’s arms are always open. That’s why you should subscribe. Each issue is a new universe, a brief time away from what Rand calls “real life” (though, I suggest, that life is no more nor less real than that found in the pages of Mineshaft). “Long live MINESHAFT!” Crumb says. How can I disagree?

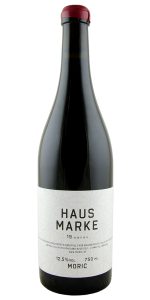

So I’m taking up my private German lessons again and searching for flights — a goal more aspirational than practical at the moment, but a boy can dream. He can also drink. I’m laying in a case of Haus Marke Red from the

So I’m taking up my private German lessons again and searching for flights — a goal more aspirational than practical at the moment, but a boy can dream. He can also drink. I’m laying in a case of Haus Marke Red from the