Marilyn and I will be raising our glasses tonight to the memory of critic, translator, and memoirist Marjorie Perloff, who cast off this mortal coil last Sunday at the age of 92.

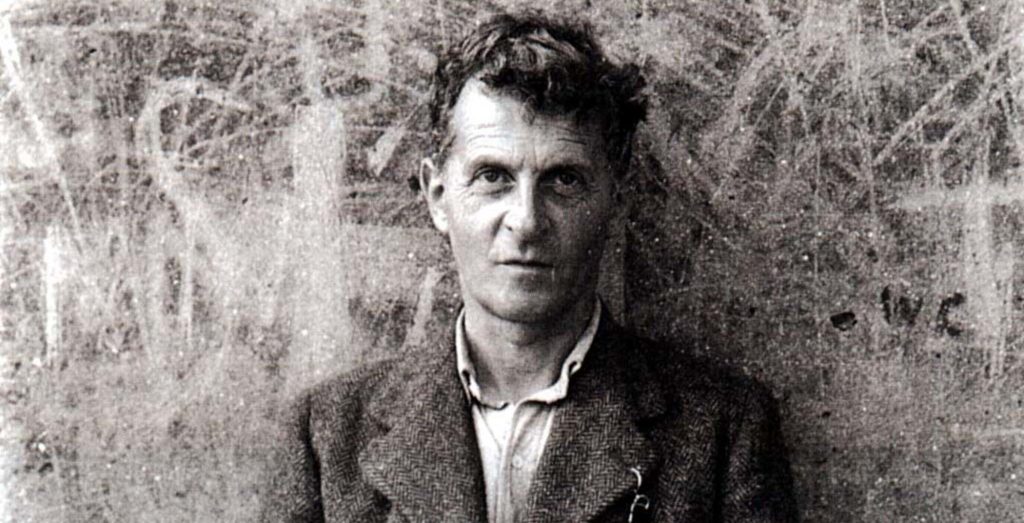

Professor Perloff was a staunch champion of the American avant-garde, especially its poets (Frank O’Hara and Charles Bernstein) and its musicians and choreographers (John Cage and Merce Cunningham). But more recently she had turned her attention to the Vienna of her youth; her 2004 memoir The Vienna Paradox is a moving, beautifully written but typically intellectually uncompromising examination of her youth and early career as an emigre from Austria, and I’ve written about her 2016 Edge of Irony: Modernism in the Shadow of the Habsburg Empire — a book that deeply affected me when I read it — here. In 2022 she published a fine translation of Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Private Notebooks: 1914-1916 (noted here), and her introduction graces a new translation of the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, published just last month and on my next-to-read list.

Clay Risen wrote the obituary for the New York Times, and an “In memoriam” written by Alan Thomas with the collaboration of Perloff’s family, the poet Charles Bernstein, and the University of Chicago Press appears here.

It’s taken a while, but it’s worth the wait: the

It’s taken a while, but it’s worth the wait: the