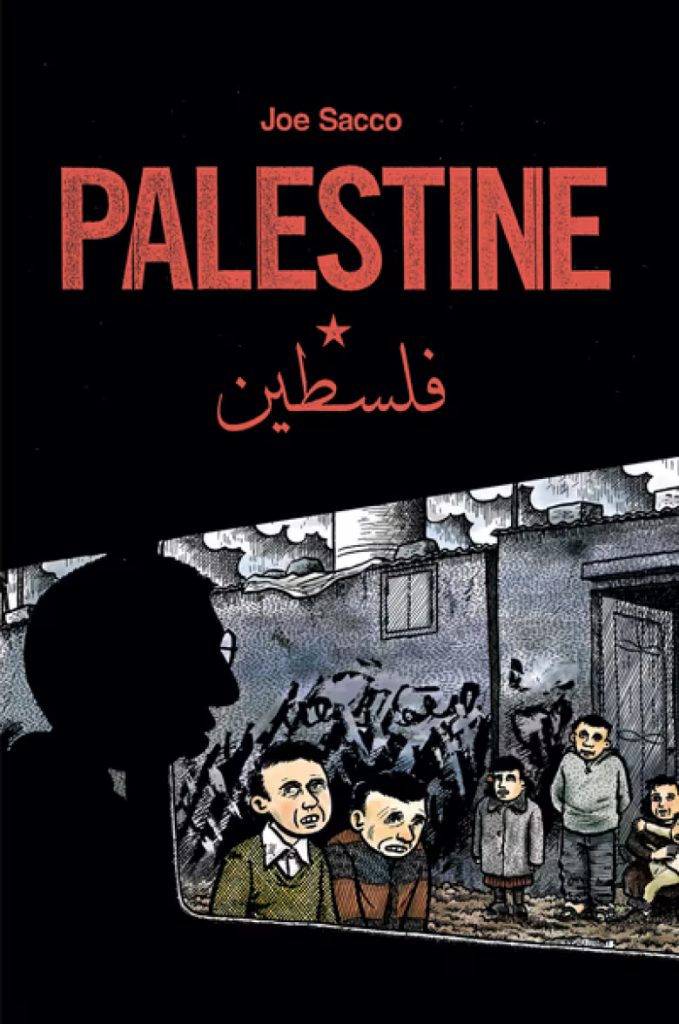

About a week after the War in Israel began, I picked up Joe Sacco’s Palestine (Fantagraphics Books, 2015), the collection of Sacco’s comic books that provided a journalistic overview of the West Bank and Gaza in December 1991-January 1992. I did this not because of any particular political sympathies associated with the war, but because I thought it important to expose myself to other historical and geographical material about the region. Comics has been one of my lifelong interests, and Sacco is among the most celebrated of the comics journalists, a pioneer in the field of using narrative comics as a means of expressing individual perspectives on world events.

Reading Palestine for the first time at this point in history was a sobering experience. Sacco, who graduated with a degree in journalism from the University of Oregon in 1981, travelled to the region as a solo writer, unassociated with any larger media outlet, and visited and interviewed a side variety of Palestinian men, women, and children over a two-month period; he also spent time in Jerusalem and Tel Aviv, getting to know a variety of Jewish and Arab Israelis as well. He emerged with a saddening chronicle — inconclusive, as all such chronicles must be, but with a deeper understanding of the tensions in the region and the recent past of the Middle East.

I also must confess that I read it as an antidote to the now-unending news cycle, more traumatic during wartime (an eternal wartime, apparently; the Russo-Ukrainian War continues, as well as a variety of conflicts in Africa and other regions, which largely go unreported in the US media). Distant from the military conflicts, I search for a deeper compassion and understanding instead — for everyone involved — and this is not something one finds in newspaper headlines, television coverage, or Facebook feeds.

I came away from Sacco’s Palestine with two notes relating to comics journalism and to independent comics generally. First, comics provide a unique worldview through the juxtaposition of word and hand-drawn image: a deeply personal expression, unique from other literary forms in that word and image always exist in a state of tension, sometimes ironic, sometimes tragic, sometimes humorous, sometimes sarcastic or satiric. In comics journalism especially this is an antidote to the single-dimension approach of prose reportage, whether that dimension is Ernie Pyle’s or Hunter S. Thompson’s. Second, that tension between word and image, between the white spaces of panels in the comics themselves, provide room for the reader to insert their own responses to what is seen and read. Sacco claims that his use of negative and positive space within an image is a response to Louis-Ferdinand Céline’s use of ellipses in his novels: a caesura, a pause, a disconnection that readers bridge themselves with their own reaction. What also emerges from these pauses, from these white spaces, is room for contemplation, for thought itself. Every reader of any literary form from verse to narrative prose to reportage, of course, participates in this, but the comics form demands further effort on the part of the reader in negotiating the relationship between word and hand-drawn image. Contemplation and meditation emerges from that negotiation. (I had the same experience, by the way, reading Daniel Clowes’s new disturbing and masterly Monica, which I hope to write about soon.)

I should also note that comics artists are also responding to another current war, the Russo-Ukrainian War; tomorrow, October 24, will see the publication from Ten Speed Graphic of Diaries of War: Two Visual Accounts from Ukraine and Russia by Nora Krug, who most recently illustrated an edition of Timothy Snyder’s On Tyranny.

Sacco’s work is a continuance of the comics form’s approach to the real world, especially about war, conflict, and anti-Semitism, and in dark days like these that approach, because it breeds complex thought, is essential to making it through our world. I only need to mention the roles that Art Spiegelman’s Maus, Keiji Nakazawa’s Barefoot Gen, and Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis have played in the maturation of the form. Although these works can’t be characterized as journalism per se, nonetheless their status as imaginative, stylized non-fiction memoirs of the terrors of war — as personal responses to armed conflict — elevates them to the level of art.