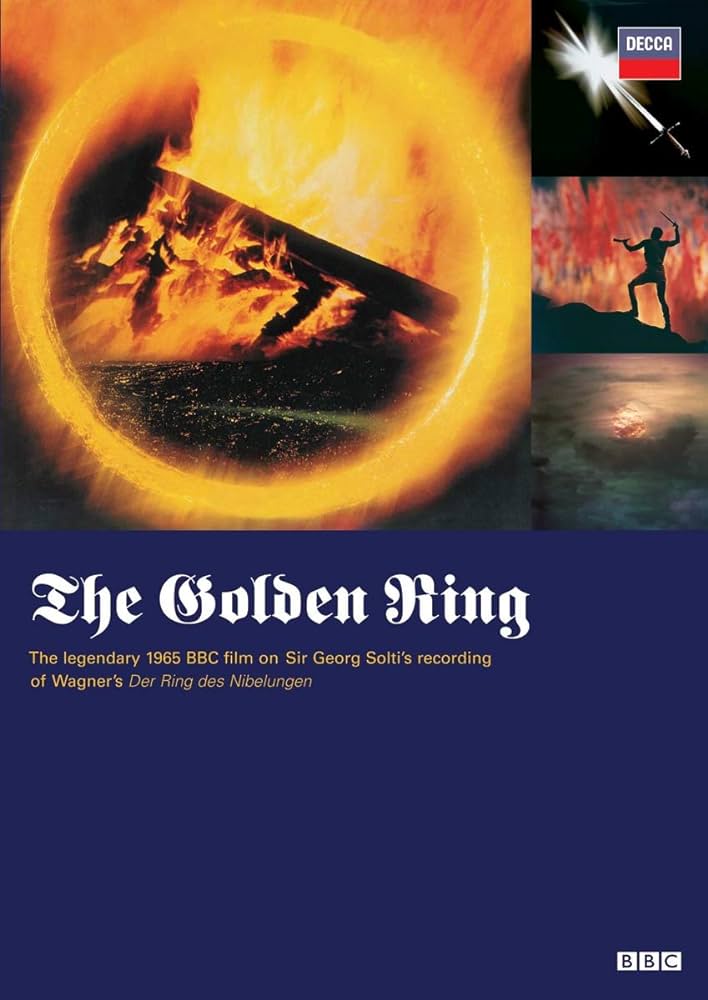

The 1964 BBC documentary The Golden Ring gathers together many of my enthusiasms into one 87-minute film: Wagner, Vienna, analog recording, and whatever pleasures all of these entail. Nearly sixty years later, it’s now a historical document of a particular moment in time, art, and technology, a portrait of one of the greatest recordings ever made of one of the great artistic achievements of the nineteenth century and, indeed, all of Western music: The Solti Ring cycle.

The Golden Ring covers the recording of the final Ring opera, Götterdämmerung; Das Rheingold had been released in in 1958 and Siegfried in 1962, with the second opera, Die Walküre, to come in 1965. All of them were recorded in Vienna’s Sofiensaal, originally built in 1826 but which was almost totally destroyed by fire in 2001 (it was finally rebuilt and renovated in 2013 and re-opened as an event space). The documentary is a rare behind-the-scenes look at a classical music recording, most notable perhaps for the ability to eavesdrop on conductor Solti and producer John Culshaw as they negotiate the daily difficulties of the project.

It’s a pleasure to watch, especially if, like me, you have the records on hand, and I must admit I’ve got them all now except, ironically, Götterdämmerung. I’ve purchased used versions of all of them from Discogs, and must say been delighted with their condition. They sound great, even now, sixty years after their release, and I’ve gotten near-mint-condition vinyl at bargain-basement prices, far less than I would have paid when I first listened to the Solti Ring in the early 1980s. I can only assume that this is because (1) they were very well taken care of, and (2) there’s little market for them. Capitalism works for me.